Rising water temperatures and the increasing levels of carbon dioxide in our oceans are killing our beautiful coral reefs at an unprecedented rate. Add the current El Niño weather pattern that is expected to prevail through winter and spring 2016 to the mix, and things look even worse. Scientists estimate that the 1988 El Niño destroyed almost 16% of the world's coral reefs and believe things could get even worse this time around.

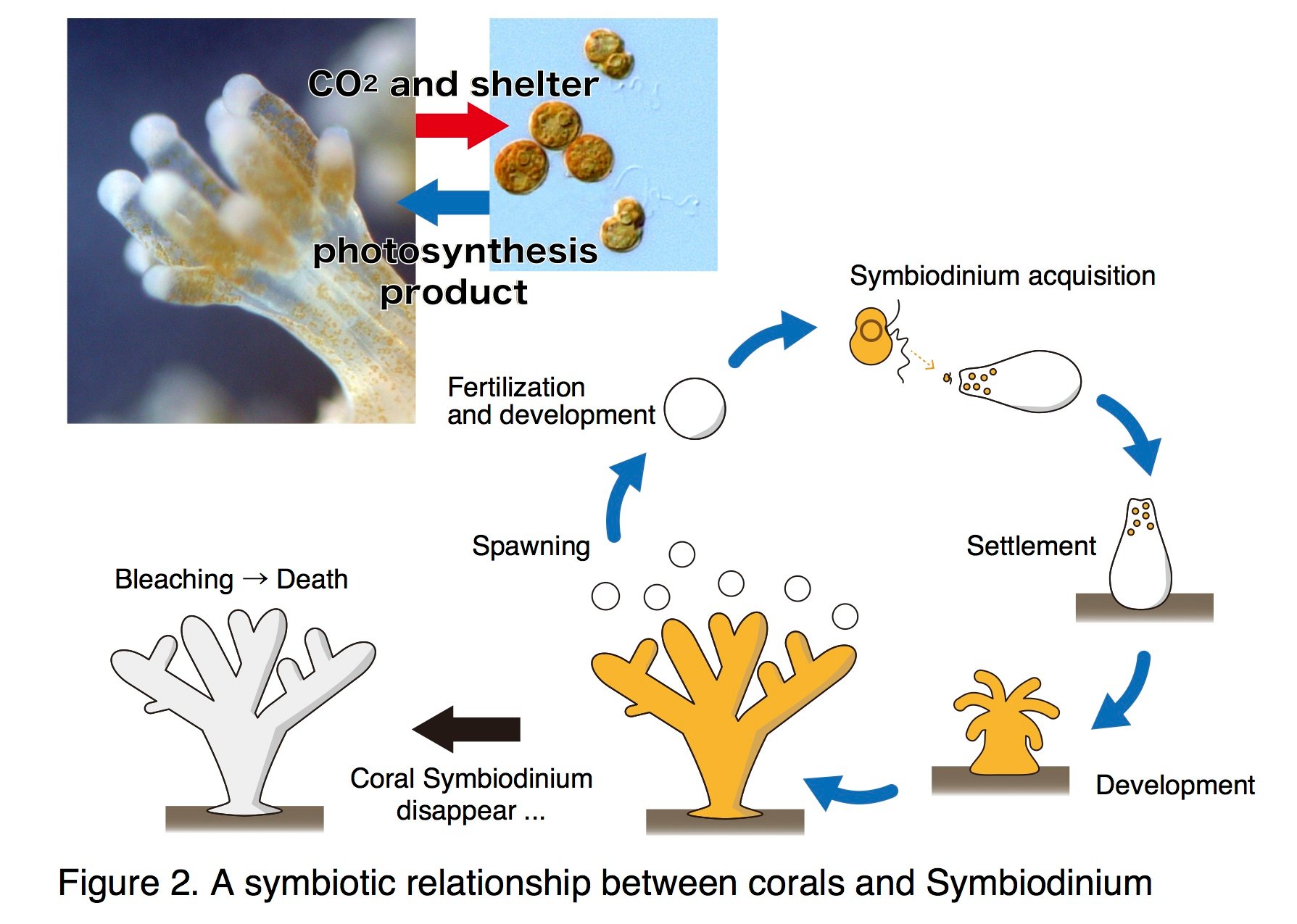

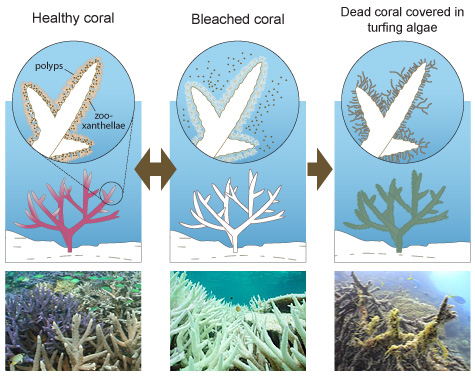

So what makes coral so vulnerable? Although it may be hard to believe, corals are not plants, but animals. The colorful reefs that we admire so much happen to be calcium carbonate skeletons discharged by colonies of hundreds of thousands of tiny polyps that live and grow together. To survive, the sedentary animals have developed a symbiotic relationship with an algae called zooxanthellae. The coral polyps give the zooxanthellae a home and in return, the algae provide the polyps with their vivid color and food.

The rising water temperatures and acidification are causing the coral polyps to reject their zooxanthellae friends. As a result, the corals are not only losing their food source but also their vivid colors, a phenomenon researchers refer to as “bleaching.” While the tiny animals can recover from mild bleaching, they are unable to survive severe or long-term bleaching.

The disappearance of the reefs does more than rob humans the chance to admire the beautiful structures. It removes a natural barrier that protects shorelines from storms and also leaves fewer habitat options for fish and other marine life.

To prevent these valuable animals from disappearing altogether, a team of researchers from the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology is attempting to breed 'super' corals.

The group led by Dr. Ruth Gates began by selecting individual coral species that seem to have adapted to the changing ocean conditions better than others. They then made them even more resilient by subjecting them to warmer, more acidic water at their research center on the 28-acre Coconut Island, in Kāne'ohe Bay off the Island of Oahu.

The resulting strains are being bred with each other to create 'super' corals that will hopefully not just withstand, but thrive in the warmer, increasingly acidic oceans. Once ready, the researchers plan to transplant the coral into Hawaii's Kaneohe Bay, which has lost an estimated 60 percent to 80 percent of its coral to bleaching this year.

Though this sounds simple enough, there is no guarantee it will work given that coral is sensitive to touch and also breeds very slowly and infrequently. Also, past attempts to transplant coral have failed because they were either gobbled up by parrot fish or succumbed to the disease. Even if it works, some experts are concerned that populating the reef with just a single species of coral will lower the ocean's biodiversity, making the tiny animals more susceptible to disease.

Although the researchers realize the dangers, Gates believes there is no choice but to intervene if we want to prevent the reefs from disappearing altogether. Tom Oliver, a marine biologist and team leader at NOAA's Coral Reef Ecosystem Division agrees. The expert who believes the project is both scalable and promising says, "The question is not can they do it, it's can they do it fast enough?" - We sure hope so!

Resources: huffingtonpost.com,techtimes.com,yale.edu