Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and important ecosystems on Earth. Not only do they provide food and habitats for the fish and seafood we eat, but they also shelter many other organisms that are crucial for ocean food chains. Experts estimate coral reefs contribute about $30 billion USD to the global economy annually, through tourism, fisheries, and coastal protection. Unfortunately, warming ocean waters, acidification, and over-fishing are killing the beautiful reefs at unprecedented levels.

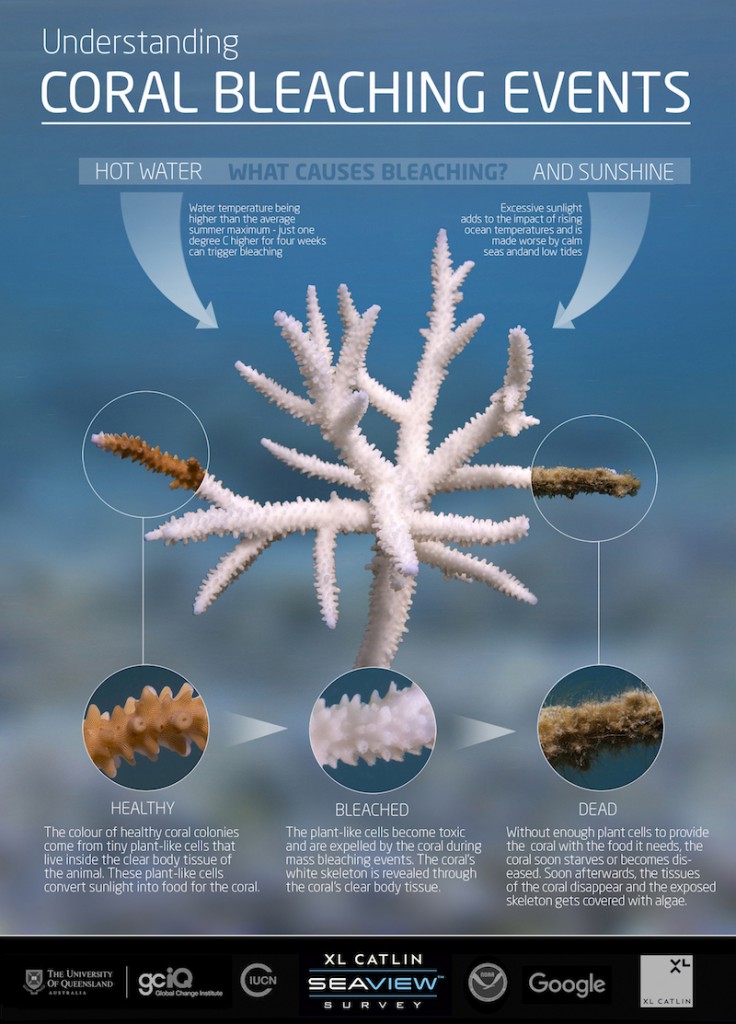

So why are coral so vulnerable? As you may know, corals are not plants, but animals. The colorful reefs that we admire are calcium carbonate skeletons discharged by colonies of hundreds of thousands of tiny polyps that live and grow together. To survive, the sedentary animals have developed a symbiotic relationship with the zooxanthellae. The coral polyps give the zooxanthellae a home, and in return, the algae provide the polyps with their vivid color and food.

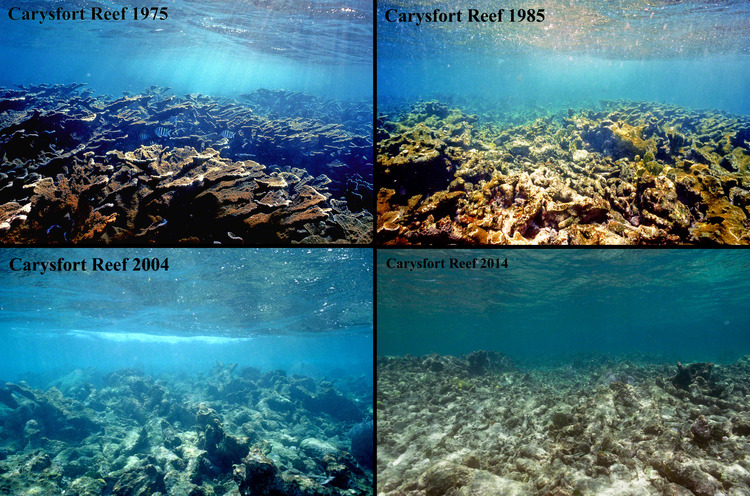

The rising ocean temperatures and acidification, are causing the coral polyps to reject their zooxanthellae friends. As a result, the corals are not just losing their food source but also their attractive coloring; a phenomenon researchers refer to as “bleaching.” While the tiny animals can recover from mild bleaching, they are unable to survive when it continues for an extended period of time. On October 18, Australia’s Great Barrier Reef Authority, which monitors the world’s largest coral system, reported that the reef had lost 22% of its coral this year, the worst mass bleaching event on record.

Past reef restoration efforts have all been focused on growing and repopulating the coral underwater. Now, a new startup called Coral Vita seeks to establish coral farms on land using a technique called micro-fragmentation. Developed by David Vaughn, the Director of the Center for Coral Research at Florida’s Mote Marine Laboratory, the process entails splitting the coral into tiny pieces, which causes it to repair and regenerate. When the regrown pieces are placed next to each other, they merge and form larger sections, which can be transplanted into the ocean to replace dead coral.

Vaughn, who has been working to perfect micro-fragmentation for over a decade, says the coral grows 25-40 times faster than with traditional methods and is more efficient at merging into large colonies. What’s even more encouraging is that the land-cultivated coral has a 90% survival rate when transplanted in the ocean. Also, growing coral under monitored conditions provides researchers the opportunity to breed hardier species or “super corals,” which can withstand rising temperatures and water acidification.

Coral Vita’s first attempt to use micro-fragmentation outside the laboratory will begin in 2017 on a stretch of beachfront property in the Dominican Republic. The founders say the location provides easy access to ocean water for the farm and enables them to educate tourists about the importance of conserving coral reefs.

If successful, Coral Vita plans to expand the program and use the land-grown coral to repopulate the reefs along the coastline of the Dominican Republic. While this project will not single-handedly save the world’s coral reefs, it is an important first step, one that will hopefully lead to others to join this valiant conservation attempt. As company co-founder Sam Teicher says, “You can’t be entrepreneurs without being optimists.”

Resources: Fastcompany.com,mote.org, coralvita.com