Researchers have long maintained that we sleep to accomplish a neural or physiological function that cannot be completed when awake. Why else would higher animals waste a third of their lives sleeping when they could be doing more important things like looking after their families, working, or hunting? Some scientists believe sleeping helps recharge the body, while others think it is important for consolidating newly-formed memories. Now, there is new evidence which suggests that the purpose of sleep may be to forget some of the millions of new things we learn each day.

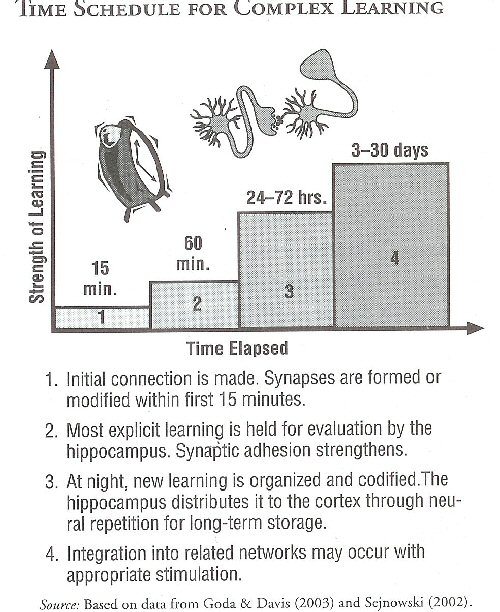

The neurons in the human brain comprise fibers called dendrites. These grow as we learn new things and connect the brain’s cells to each other at contact points called synapses. The larger the dendrites become and the more cells they connect, the more information we retain.

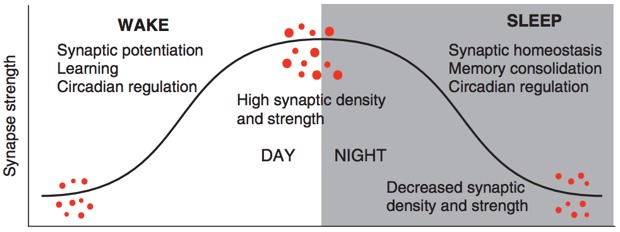

In 2003, Giulio Tononi and Chiara Cirelli, both biologists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, proposed an interesting new idea. They hypothesized that the number of things our brains learn each day result in so many connections, or synapses, that things start to get a little muddled. The scientists said that sleeping allows us to sort through the “noise” and dispense all the unnecessary information, leaving behind only the most important memories. Since then, the researchers have found plenty of indirect proof to support their “synaptic homeostasis hypothesis.”

However, the university’s most recent research, published in Science on February 2, 2017, provides direct evidence to support the theory. The experiment involved analyzing 6,920 synapses in the brain shavings from two groups of mice over a four-year period; one group had been allowed to sleep, while the other had been kept awake and stimulated with toys. The team, led by University lab assistant Luisa de Vivo, discovered that the brain shavings of the sleeping mice had nearly 20 percent fewer synapses than those that had been kept awake and entertained.

A second, entirely separate, study led by Graham H. Diering, a postdoctoral researcher at Johns Hopkins University, found similar evidence through a different approach. The team began by using a chemical to light up the surface proteins of the synapses in mice brains. They discovered that the number of surface proteins declined while the mice were asleep, indicating the synapses were indeed shrinking. Particularly intriguing was a protein called Homer1a.

In prior lab studies on neurons, the researchers had found that this protein plays a significant role in trimming synapses. They wondered if Homer1a was as effective during sleep as well. To investigate, Diering and his team genetically engineered mice that were incapable of producing the Homer1a protein and observed their synapses as they slept. Sure enough, there was no change in the brain proteins of these mice.

But did the protein pruning have any effect on learning and memory? To investigate, the researchers created two groups of mice. One was injected with a chemical that blocked Homer1a, while the control group was left unaltered. They were then placed in a room where contact with certain portions of the floor resulted in a mild electric shock. The rodents were then allowed to sleep. When the researchers took the mice back to the room the following day, they noticed that both, the control and test group, froze in fear.

However, the reactions were very different when they were transferred to a room where there was no electric shock. The control mice instantly started to sniff around and explore their new surroundings. The test rodents, however, remained in a corner, still suffering from memories of the previous day.

The scientists, who published their findings in Science on February 3, 2017, believe the mice with blocked Homer1a protein could not clear their brains and, were, therefore, unable to distinguish between the two rooms. The control group had been able to dispose of all irrelevant information and could sense the difference easily.

It was also evident during the study that the brain does not trim every synapse. 20% of neurons remained unchanged; these were most likely well-established memories. Hence, although we may be sleeping to forget some of what we’ve learned, the brain “forgets” in a smart way.

While these studies provide compelling evidence of “synaptic homeostasis hypothesis,” most researchers believe clearing our brains is not the only purpose of sleep. Resting our minds and bodies has also been found to help with other biological functions like strengthening our immunity and aiding digestion. Though scientists may never agree on a single reason, they are all sure of one thing — a good night’s rest is essential for our well-being. So try and spend at least a third of your day sleeping!

Resources: sciencealert.com, the guardian.com, Sciencemag.org