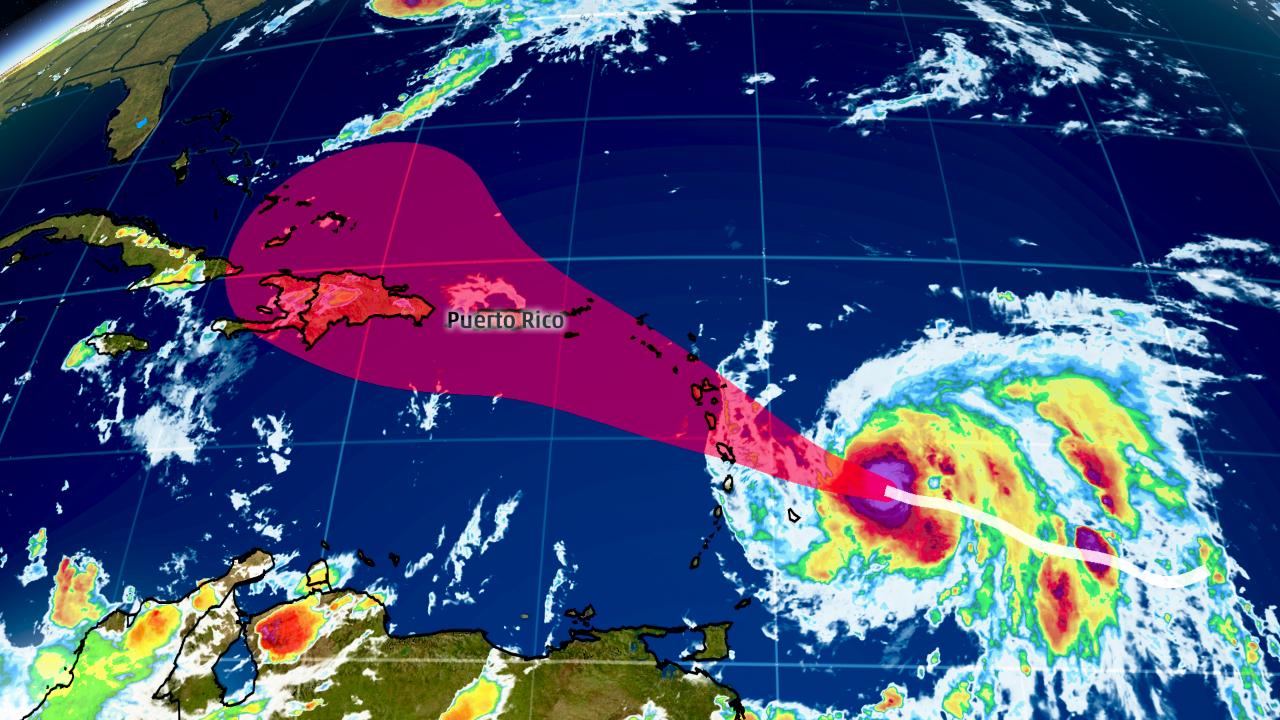

Harvey, Irma, Jose, and Maria — these seemingly innocuous names all belong to powerful hurricanes that have devastated small islands and major US cities in the past few weeks. Maria, the latest Category 5 storm, began its path of destruction by pummeling the Commonwealth of Dominica, a tiny sovereign island country in the Caribbean, on Tuesday, September 18. Two days later, on September 20, the slightly weakened Category 4 storm unleashed its wrath on Puerto Rico, which was still reeling from the impacts of Irma.

The strongest hurricane to hit the US territory in 89 years, Maria has flooded homes and businesses with as much as seven to ten inches of water and destroyed the island’s already fragile electricity lines. All residents remain without power and there is no estimate on when it will be restored. Eighty-five percent of the 1,600 cellphone towers, and a majority of the above-ground and underground phone and internet cable lines have been destroyed. Officials say they have been unable to communicate with 40 of the 78 municipalities since Maria struck. To make matters worse, on Saturday, September 23, over 70,000 residents were evacuated because of the possible breach in the Guajataca Dam that holds back a manmade lake, created to provide residents with fresh water.

Meanwhile, Maria, which has now further weakened to a Category 3 storm, continues to wreak havoc. After bringing heavy rains and high surf surges to the Turks and Caicos Islands and the Bahamas, the storm is now making its way toward the US East Coast and Bermuda. Hopefully, like the rest of us, Maria is tired of all the destruction and will fizzle out by the time it gets there.

The consecutive string of deadly hurricanes has led to the perception that 2017 may be the worst hurricane season yet, while providing fuel for the ongoing debate about the effects of global warming. Read on to find out what experts think about these assumptions.

2017 hurricane season was expected to be busier than previous years.

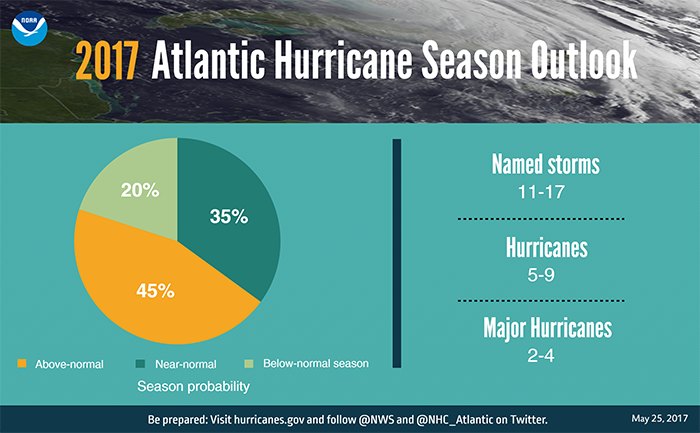

In May, experts from NOAA predicted that this year’s hurricane season, which officially begins in June and ends in November, would be more active than previous years. Their forecasts called for between 11 to 17 named storms, higher than the historical average of 12. Of these, 5 to 9 were predicted to become hurricanes, with 2 to 4 classified as a major category 3 or above storms. The agency officials said, "The outlook reflects our expectation of a weak or non-existent El Niño, near, or above-average, sea-surface temperatures across the tropical Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, and average, or weaker-than-average, vertical wind shear in that same region."

This was bad news, right?

Not necessarily. A larger number of hurricanes does not always mean more destruction, or, vice versa. That’s because forecasters can never predict the direction they will take. For example, in 1992, there were only six named hurricanes and one subtropical storm. It just took one, Hurricane Andrew, to made landfall as a Category 5 and devastate South Florida. Conversely, in 2010, there were 19 named storms and 12 hurricanes. However, none came anywhere close to the US mainland.

Back to the question – Has 2017 been the worst year for hurricanes yet?

Experts say that depends on how you think about the storms. So far this year, we have experienced just 13 named tropical storms, or less than half of the 28 that formed in 2005, the most active season yet. However, what makes this year unusual is that in the 166 years of weather record keeping, the US has never been hit by two Atlantic Category 4 or higher hurricanes in the same year.

Tom Schmidlin, a meteorologist and professor at Kent State University says, “Sometimes these big storms will turn and not hit any land, but this year, we’ve had the bad luck of these storms hitting the Caribbean islands and then coming right into the US.”

Is climate change responsible for the destructive hurricanes?

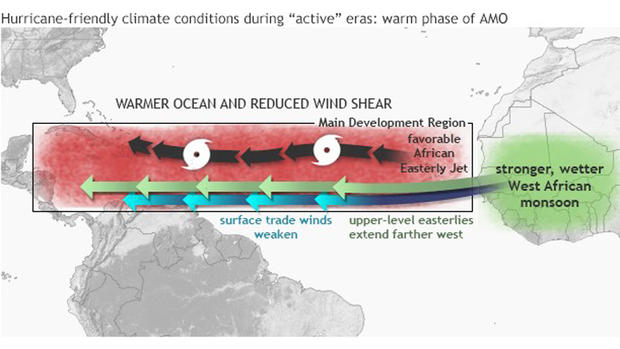

Experts say that storms are a result of both manmade and natural causes. As you are probably aware, for hurricanes to form there has to be some weather disturbance — such as a thunderstorm — warm atmospheric air, and the ocean surface temperature has to be 80° Fahrenheit (27° Celsius) or higher.

Though the higher than average summer temperatures on the eastern tropical Atlantic Ocean, where most hurricanes form, did provide the storms with more fuel, they have also been helped by the lack of wind shear — fast-blowing winds that usually help break them up. Hence, it is not accurate to attribute the powerful hurricanes entirely to global warming.

What can we do?

Unfortunately, not much, at least when it comes to preventing the storms from hitting land. We can, however, help scientists in their efforts to reverse climate change and cool down the oceans by making small changes like switching off unnecessary lights or biking to school.