The reason animals “waste” so much time sleeping has always been somewhat of a mystery to scientists. The popular belief is that resting rids brain cells of toxins, helps consolidate fresh memories, and prepares the mind for a new day of learning. However, a new study by research students at the California Institute of Technology has unveiled it’s not just creatures with brains that snooze - even the brainless jellyfish need their zzz’s!

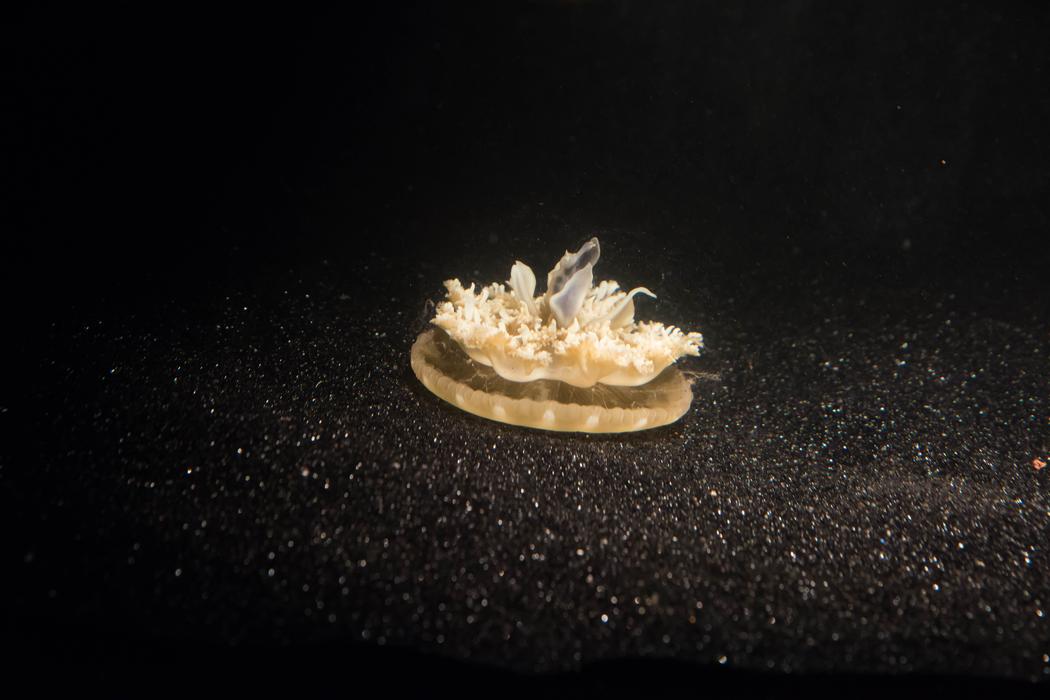

Ravi Nath, Michael Abrams, and Claire Bedbrook began by populating a home aquarium with 23 specimens of the Cassiopea jellyfish. The largely immobile creatures spend their lives on the seabed, or clinging to other surfaces, with their stinging tentacles facing upwards to catch any unsuspecting prey that swims past.

The researchers, who used cameras to record the movement of the jellyfish for six days and nights, observed that the animals were 30 percent less active at night. They not only pulsated less frequently, but also underwent periods of between 10 to 20 seconds of no movement at all.

However, to ascertain that the gelatinous animals, which have inhabited Earth for over 650 million years, were sleeping and not merely resting, they had to test for three requirements. The jellyfish should be disoriented when disturbed gently during their slumber, become active when awakened vigorously, and finally, like most animals, be unable to function normally without adequate sleep.

The team began by gently moving the snoozing jellyfish from their preferred resting spot at the bottom of the tank to the surface. They observed it took some time before the animals swam back to their original sleeping area, proving they were disoriented. In contrast, when the action was repeated 30 seconds later, the now fully-awakened animals instantly returned to the bottom, establishing the second requirement of sleep. To test how the creatures react to lack of sleep, the students kept the jellyfish awake the entire night by blasting them with jets of water every twenty minutes, Sure enough, they were less active the following day. The same behavior was not observed when the animals were disturbed with the jets during the day.

While the study is impressive, not everyone is convinced that it proves the jellyfish were sleeping. Anders Garm, a neuroscientist at the University of Copenhagen, says, “I would hesitate to call it sleep until you actually look at what happens in the nervous system.” He believes there may be other factors, such as light, that could be causing the change in pulsating activity. Cheryl Van Buskirk, a geneticist who studies sleep at the California State University in Northridge, disagrees, saying, “These data strongly argue for the existence of sleep in Cassiopea.” She speculates, “It [sleep] may be an inherent requirement of excitable cells.”

The researchers, who published their findings in the journal Current Biology on October 7, next plan to test if humans and jellyfish share similar sleep genes. A preliminary experiment, done by exposing jellyfish to a sleep-inducing medicine used by humans, appeared to work on the animals as well. However, further research needs to be done to confirm the theory.

If the team is able to prove unequivocally that the primitive jellyfish, which have been untouched by evolution, need to sleep, it may establish that sleeping serves a purpose even more complex than currently believed. Abrams thinks by studying the jellyfish, “We might be able to get at those core, fundamental components of why something sleeps.”

Resources: theatlantic.com,cambridgebrainscience.com, sciencenews.org