While elephants born without tusks are not unheard of, they normally comprise just 2 to 6 percent of the herd population. However, that is not the case at Mozambique’s Gorongosa National Park, where an astounding 33 percent of female elephants born after the country’s civil war ended in 1992, are tuskless. While that may appear to be just a coincidence, Joyce Poole, an elephant behavior expert and National Geographic Explorer, has another theory. The researcher thinks we may be witnessing an unnaturally induced evolution of the species due to the incessant poaching of the mammals for their valuable tusks.

Tusks are overgrown upper incisors which protrude from sockets in the elephant’s skull. Unlike our permanent teeth, they continue to grow throughout the animal’s life, becoming longer and thicker with age. While humans covet them for ornamental purposes, the teeth are an essential survival tool for elephants. The mammals use tusks for a variety of tasks including, extracting tree bark, digging for water or roots and, in the case of males, even fighting with one another. While poachers usually first target older males due to their impressive tusks, females are not spared either. As a result, in areas where poaching goes unchecked for extensive periods of time, the proportion of tuskless females increases. This allows them to gain a biological advantage, resulting in a larger than average population of female offspring with no tusks.

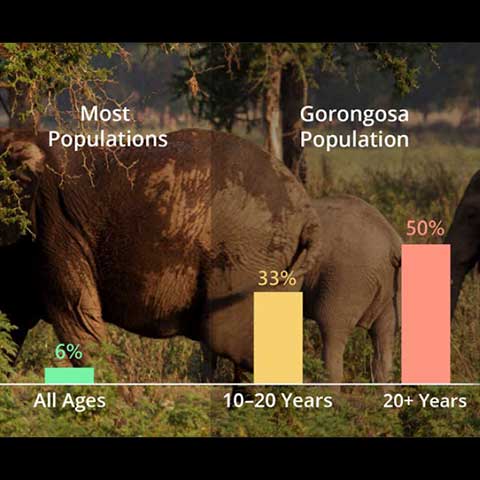

Poole, who also serves as scientific director of nonprofit ElephantVoices, believes this phenomenon explains the unprecedented rise in the number of tuskless females at Gorongosa National Park. The researcher, who has been studying the wildlife sanctuary’s elephant population for many years, says prior to the country’s 15-year-long civil war, the 100,000 acre-park was home to over 4,000 pachyderms. However, by the time the conflict ended in 1992, about 90 percent of the mammals had been slaughtered for ivory to help finance weapons and meat to feed the soldiers. Of the less than 200 survivors, over 50 percent of the females – 25 years or older – had no tusks. Hence, it is not surprising that the park’s tuskless elephant population has grown substantially.

This is not the first time researchers have observed a drastic change in the population of elephant herds who have suffered severe poaching losses. At the Ruaha National Park in Tanzania, an area which was heavily poached in the 1970s and 1980s, 35% of elephants 25 years or older and 13% of those younger than 25 are now without tusks. A 2008 study published in the African Journal of Ecology found that the number of tuskless females at Zambia’s South Luangwa National Park and adjacent Lupande Game Management Area went from 10.5 percent in 1969 to almost 40 percent in 1989, largely due to illegal hunting for ivory.

Thus far, the genetic consequence of poaching has largely impacted female elephants. Poole explains, “Because males require tusks for fighting, tusklessness has been selected against in males, and very few males are tuskless. For African elephants, tuskless males have a much harder time breeding and do not pass on their genes as often as tusked males.”

However, if the slaughtering of males with the most impressive tusks continues at this pace, it could result in a generation of elephants with much smaller tusks. Poole says, “Assuming that poachers select according to tusk size, they will tend to kill older males with very large tusks, thereby taking out of the population of breeding-aged males who also happen to have very big tusks. Those males then no longer pass on their genes for large tusks. In this manner, heavy poaching will select out genes for large tusks.”

The recent ban on ivory in both the US and China should help eliminate, or at least reduce, elephant poaching. However, scientists are not sure how long it will take for the herds with a higher rate of tuskless females, to reverse the trend.

The only silver lining is that the tuskless elephants look healthy, indicating they have learned to adapt without their all-important “tools.” To investigate how the pachyderms are able to thrive without tusks, a team led by University of Idaho researcher Ryan Long recently fitted six adult females, three with tusks and three without, with GPS tracking devices. The researchers plan to monitor the animals for a few years to document the tuskless mammals’ modified lifestyle and assess its impact on the surrounding environment.

Resources: Nationalgeographic.com, awf.org