Thanks to its harsh environment, Antarctica remained largely untouched by humans for many millennia, allowing a thriving ecosystem to evolve. However, since the 1990s, the last true wilderness on the planet is becoming an increasingly popular destination for adventure-seeking tourists. Now, a new study asserts that the visitors may be leaving behind harmful bacteria which could devastate the area’s native bird population.

While we mainly hear about zoonoses – diseases like Ebola, the Zika virus and swine flu – that are transmitted from animals to humans, the reverse also holds true. Humans can infect animals with ailments such as mumps, salmonella, and even the flu. Researchers, however, believed that the Antarctic fauna, which had no recorded reverse zoonoses cases, was immune to the danger due to the continent's extreme weather. However, microbiologist Marta Cerdà-Cuéllar at the Research Center for Animal Health in Barcelona, Spain, was not convinced this was true.

She and some colleagues decided to examine fecal samples from Antarctic birds for evidence of human bacteria. To ensure the waste was not contaminated, the scientists had to collect it from the birds themselves. This was no easy task, given that it meant not only catching the animals, but also sterilizing them with swabs. “Penguins are very strong … and skuas are extremely clever,” says Jacob González-Solís, an environmental and evolutionary biologist from the University of Barcelona, who was on the team. The researcher said if they missed catching a skua at first go, the bird never came close again.

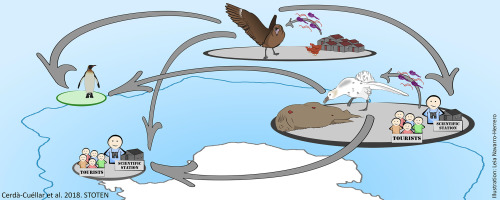

It took the scientists four years, from 2008 – 2011, to collect fecal samples of 666 adult birds from 24 local species, such as rockhopper penguins, Atlantic yellow-nosed albatrosses, and giant petrels. However, it was well worth the effort. The results of their study, published in the online journal Science of the Total Environment on October 23, 2018, revealed the presence of several types of human bacteria in the bird waste. This included gastrointestinal pathogens like the Campylobacter jejuni DNA, a common strain of bacteria that causes food poisoning in humans, and ones responsible for salmonella. The researchers say the bacteria strains were resistant to commonly-used human antibiotics, indicating they were brought in by the visitors, rather than migratory birds.

“These Salmonella and Campylobacter strains, which are a common cause for infections in humans and livestock, do not usually cause death outbreaks in wild animals,” says González-Solís. “However, the emerging or invasive pathogens that arrive to highly sensitive populations – such as the Antarctic and Subantarctic fauna – could have severe consequences and cause the local collapse and extinction of some populations." The researcher also fears the presence of these bugs could foreshadow the arrival of other, more deadly, pathogens as the number of tourists people increase.

While the best solution to prevent a catastrophe would be to stop tourism altogether, ornithologist Kyle Elliott at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, who was not involved in the new study, believes that is impossible. “One reason that Antarctica remains largely protected is because of lobbying from tourist and scientific groups,” he says. “While we should do as much as possible to reduce transmission, it’s hard to believe that we will stop tourism and science at these sites, and so it is hard to believe that humans won’t continue to transmit pathogens.”

Experts, including González-Solís, believe the only way to prevent the mass destruction of the birds is to impose stricter regulations or, at least, enforce the ones already in place. For example, while the Antarctica Treaty stipulates visitors carry their waste back home to safeguard the pristine environment, the regulation is rarely enforced. Hopefully, officials will take steps to protect the vulnerable birds before it’s too late.

Resources: sciencemag.com,mnn.com,phys.org.