Though wildfires are a common occurrence during California’s hot, dry summers, the state’s biggest fires don’t usually strike until August. However, this year, the season started early, in February, with the Pleasant Fire that took about six weeks to contain and scorched over 2,000 acres. Since then, there have been over 20 blazes across the state. However, none have been as terrifying as the Carr Fire that is currently wreaking havoc in Northern California’s Shasta County.

Ignited by a vehicle’s mechanical failure in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest on July 23, the 45-square-mile Carr Fire initially appeared to be well under control. However, things took a turn for the worse on Thursday, July 27, after the intense heat from the blazes and the 60 mph wind gusts gave rise to “fire tornadoes.”

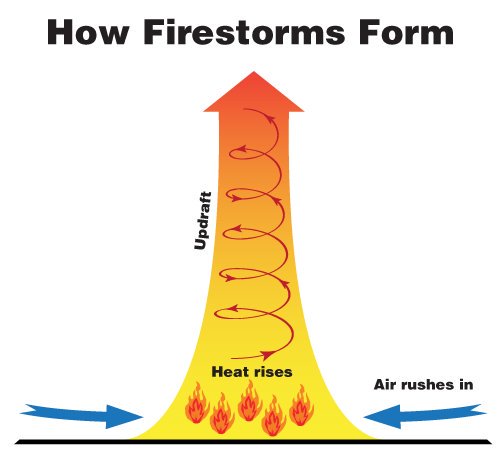

Also called fire whirls or firenados, the natural phenomena occur when the ground-level air, superheated by the flames, rises. The void left behind is instantly filled by cold air. As more and more air gets pulled in, it begins to rotate, creating a tornado-shaped spiral of flames as it comes in contact with the fire. In addition to toppling trees and blowing off rooftops, the powerful “tornadoes” also lift burning embers into the atmosphere. The winds carry the embers to surrounding areas, resulting in new fires that are miles away from the center. The floating embers also enable the wildfires to jump rivers, highways, and fire breaks.

In the case of the Carr Fire, the tornadoes increased the blaze’s intensity, making it erratic and hard to control. On Thursday night, the now fast-moving fire jumped across the Sacramento River and reached the subdivisions of Redding, forcing many of the city’s 92,000 residents to flee their homes with little warning.

To make matters worse, the extreme heat from the wildfire is producing rare mushroom-cloud-like formations known as pyrocumulus clouds. They are similar to regular cumulus clouds, except that the rising ground air gets its energy from the flames, not the sun. The hot air also contains moisture evaporated from the burning vegetation. Formed when the warm moisture-laden air meets the cooler atmospheric air, the towering clouds generate thunderstorms, lightning, and localized winds, making the fire even more volatile and harder to predict.

As of July 31, the Carr Fire, already the seventh most destructive in California’s history, has scorched over 100,000 acres and destroyed more than 1100 structures, including 723 homes. The wildfire has also claimed six lives, including those of two firefighters. The good news is that the 3,600 firefighters who are working feverishly to battle the deadly blaze made substantial progress on Monday (July 30) night, managing to contain the blaze 27 percent, up 10 percent since Sunday (July 28) night. Hopefully, the weather will cooperate long enough for them to gain total control.

Resources: CNN.com, Latimes.com, CBSnews.com