The “Ediacaran biota,” a common name given to a large group of over 200 types of fossils that have been found across the world, have baffled scientists for decades. Over the years, researchers have debated whether the strange-looking organisms were fungi, algae, or just ancient animals that had failed to evolve. Now, some experts believe they have proof that the mysterious creatures were indeed animals, probably one of the first ones on Earth.

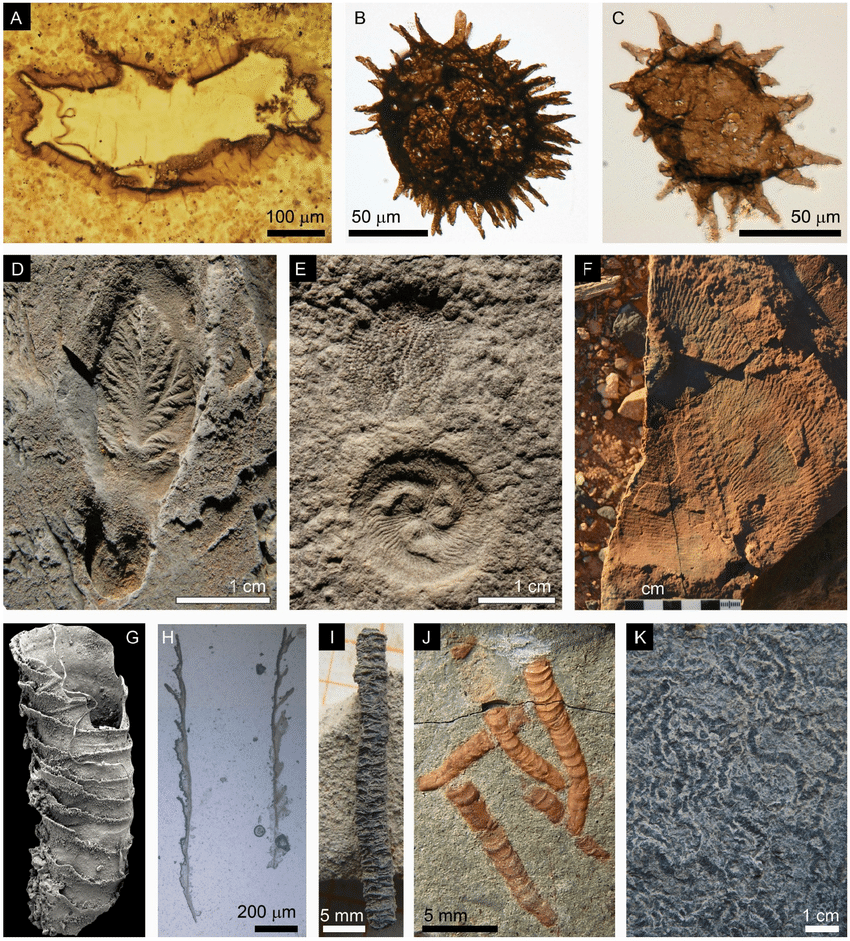

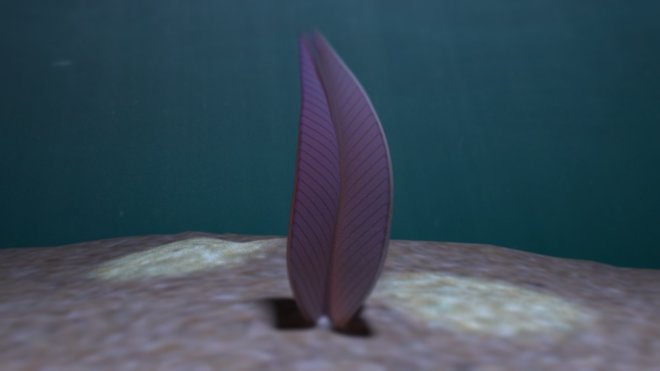

The classification confusion stems from the unique anatomy of the 43 known species of the creatures that first emerged about 600 million years ago. Some resembled simple blobs, while others looked like worms. Then there were the tube or leaf-shaped Ediacarans – complete with branched fronds that formed fractal, or never-ending patterns, with each individual sub-unit repeating the pattern of the entire frond. Since all the fossils discovered were between 571 and 542 million-years-old, scientists assumed the organisms had gone extinct just prior to the Cambrian explosion, around 541 million years ago. This was an era when ancestors of animals, such as crabs and lobsters, first made their appearance.

But a new study, published in the journal Paleontology on August 7, 2018 by University of Cambridge paleobiologist Jennifer Hoyal Cuthill, and Jian Han from Northwest University in Xi'an, China, suggests that Ediacarans were animals, some of which could move around. Though unlike any living creature on Earth today, the experts assert that the ancient animals lived beyond the Cambrian Explosion.

The researchers came to this conclusion after analyzing 200 perfectly preserved fossils of another prehistoric marine animal, Stromatoveris psygmoglena, discovered in the Yunnan province in southwestern China. Featuring multiple branched fronds, or leaf-like parts, the Stromatoveris psygmoglena, which lived during the Cambrian period about 518 million years ago, closely resemble seven Ediacaran species. The plant-like creatures, however, have always been identified as animals, primarily because they were unearthed among other fossils belonging to known animal species and preserved in a similar fashion. Cuthill says as she examined specimen after specimen, she became increasingly excited. “I began thinking: My goodness, I’ve seen these features before.”

To confirm their suspicions, Cuthill and Han used a computer to analyze the evolutionary relationships and physical features of the two groups, based on over 80 fossil photographs. The researchers found that the preserved remains of both creatures belonged to the same group in the tree of life – Petalonamae. This meant that Ediacarans were also animals. It also implied that they did not go extinct at the beginning of the Cambrian Explosion as previously believed, but survived for more than 20 million years after the important evolutionary period.

As is the case with any new discovery, not everyone is convinced of the study’s conclusions. Among the skeptics is Simon Darroch, a geobiologist at Vanderbilt University, who does not believe that Ediacarans and Stromatoveris shared the same fractal architecture. However, if Cuthill and Han’s findings hold true, it could change our understanding of evolutionary history. If Ediacarans were indeed animals, it would imply that animals began to diversify 571 million years ago, or 30 million years before the Cambrian explosion, and that they evolved successfully to the Cambrian period.

“This could mean that the [Ediacaran] petalonamids adapted more successfully to the changes of the Cambrian period than had been thought,” Cuthill writes in the Conversation, “or that the Ediacaran period and its animals were less alien and more advanced than previously realized.”

Resources: smithsonianmag.com, livescience.com, sciencemag.com