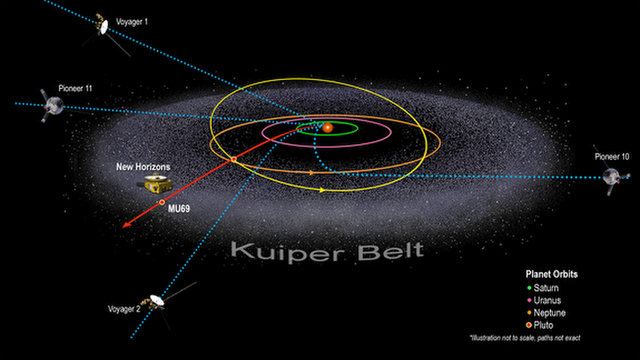

NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, launched in 2006 with a primary mission to perform the first-ever flyby of Pluto, has provided researchers with invaluable information about the dwarf planet. Now, the space probe has made more history with its January 1, 2019 flyby of distant world 2014 MU69. The close rendezvous with the icy rock, located four billion miles from Earth in the Kuiper Belt, is not only humanity’s furthest encounter with a distant object, but also the most primitive one ever visited by a spacecraft.

Nicknamed Ultima Thule for a Latin phrase meaning “beyond the known world,” 2014 MU69 is classified as a "Kuiper Belt Object.” NASA researchers believe the ring of icy worlds, located beyond Neptune, is a "region of leftovers from the solar system's early history.” Discovered by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2014, it was identified as New Horizons’ next target after the spacecraft completed its flyby of Pluto on July 14, 2015.

The main draw of investigating Kuiper Belt Objects, like Ultima, is their primordial nature. Alan Stern, the NASA planetary scientist leading the deep space mission, said, “The object is in such a deep freeze that it's essentially preserved from its initial formation. Everything that we're going to learn about Ultima, from its composition to its geology to how it's assembled, is going to teach us about the original formation conditions of the solar system."

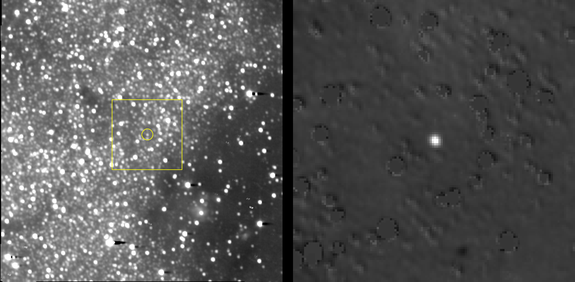

Traveling at a rapid speed of 32,000 mph (51,500 km/h), New Horizons got to within 2,200 miles of its target at the scheduled 12:33 a.m. EST on January 1, 2019. However, thanks to the 4-billion-mile distance, it took almost 10 hours for mission control researchers at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland to receive the signal from the spacecraft indicating it was healthy and had filled its data recorders with essential information on Ultima.

"We have a healthy spacecraft," said mission operations manager Alice Bowman. "We've just accomplished the most distant flyby. We are ready for Ultima Thule science transmission."

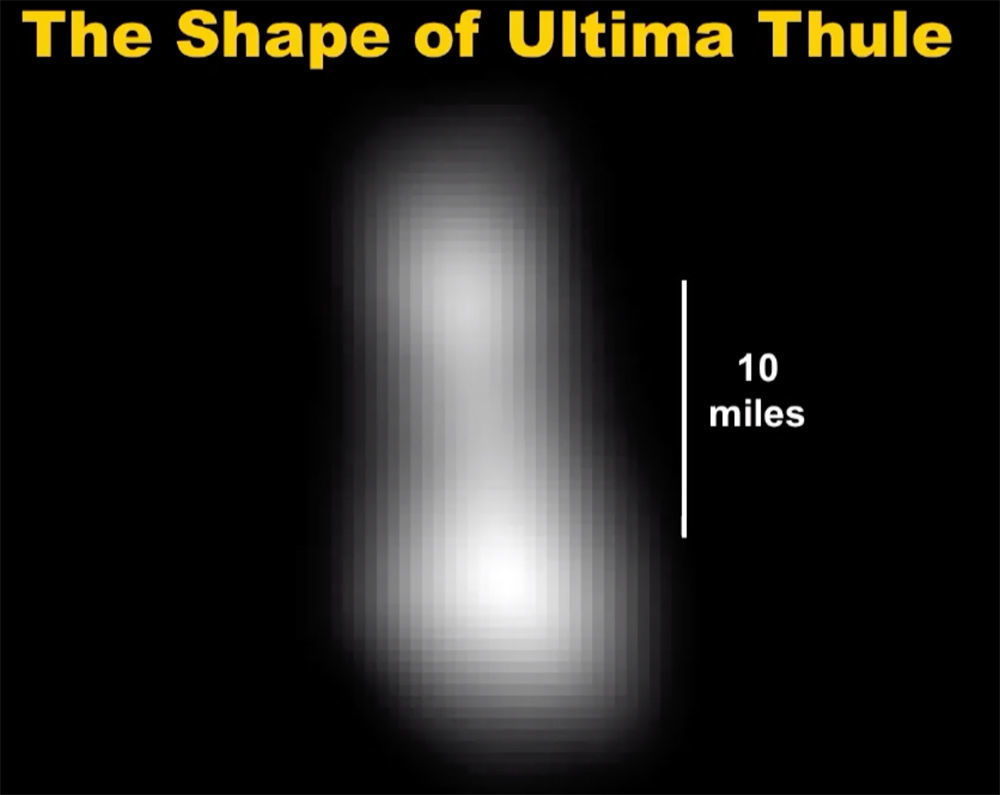

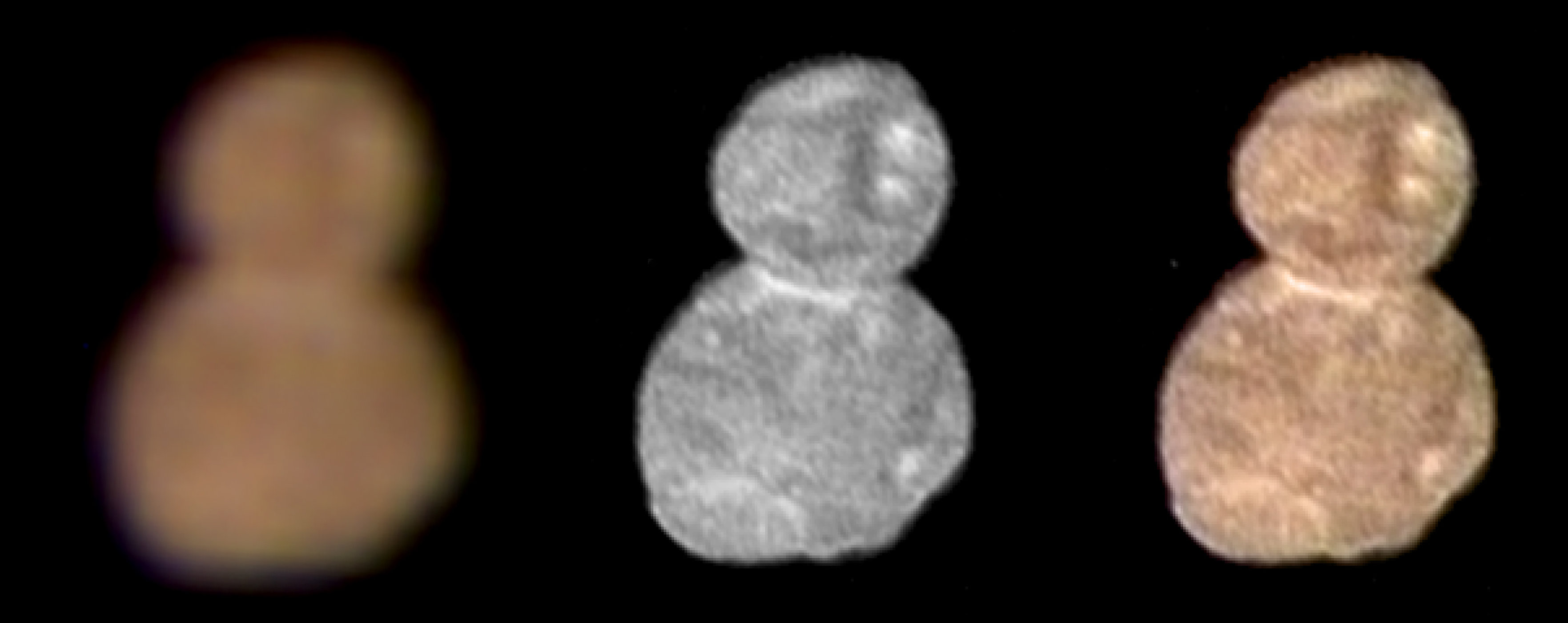

Initial images of Ultima, taken by the spacecraft as it was approaching the distant world, seemed to indicate the approximately 20-mile-by-10-mile (32-km-by-16-km) icy world was shaped like a bowling pin, with two lobes connected by a center mass. However, new photos received after the close flyby shows they are attached tightly together. “That bowling pin is gone,” said Stern. "It's a snowman if it's anything at all."

Even more interesting, the icy lobes, which have respectively been named “Ultima” and “Thule,” are red. The scientists believe the discoloration is likely caused by the same deep-space radiation responsible for the reddish hues sported by Pluto and its largest moon, Charon. They hypothesize that Ultima and Thule were once separate free-flying objects that came together gently, similar to a spacecraft docking, shortly after the solar system’s birth.

Stern estimates that given the distance, it will take the spacecraft about 20 months to transmit the “literally hundreds of images and spectra and other data types” captured during the quick flyby. Once all the information is in, the researchers will be able to reveal further details about the icy world, including its topography and if it hosts moons, rings, or something altogether unexpected.

“This is unknown exploration; anything is possible,” said John Spencer, the mission’s deputy project scientist. “Anything is possible out here when you're exploring a new class of world that you haven't seen before."

Meanwhile, the researchers are contemplating extending New Horizons’ mission to at least 2021 and finding it a new target that will help provide further insights into the Kuiper Belt region.

Resources: Space.com, solarsystem.nasa.gov smithsonian.com