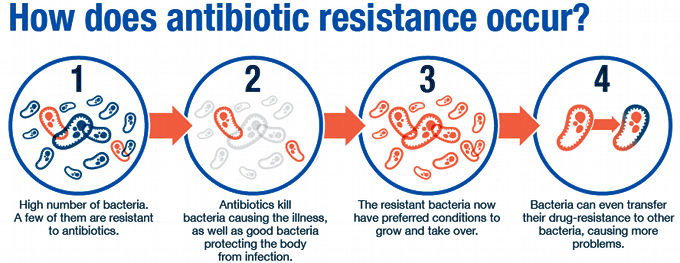

Antibiotics — medications that destroy or slow down bacteria growth — are becoming increasingly less effective as the pathogens find new ways to evade the drugs. Some produce pumps that flush the antibacterial medicines out from the bacterial cell, while others modify themselves, so they are unrecognizable as targets. Now, researchers at UK's Newcastle University have recorded the germs shedding their outer skins and changing their shapes to avoid detection.

Most bacteria are surrounded by a cell wall. The outer layer, which is akin to the human skin, protects the organisms against environmental stresses and prevents the cell from bursting. It also helps the human immune system flag the pathogen as a foreign entrant.

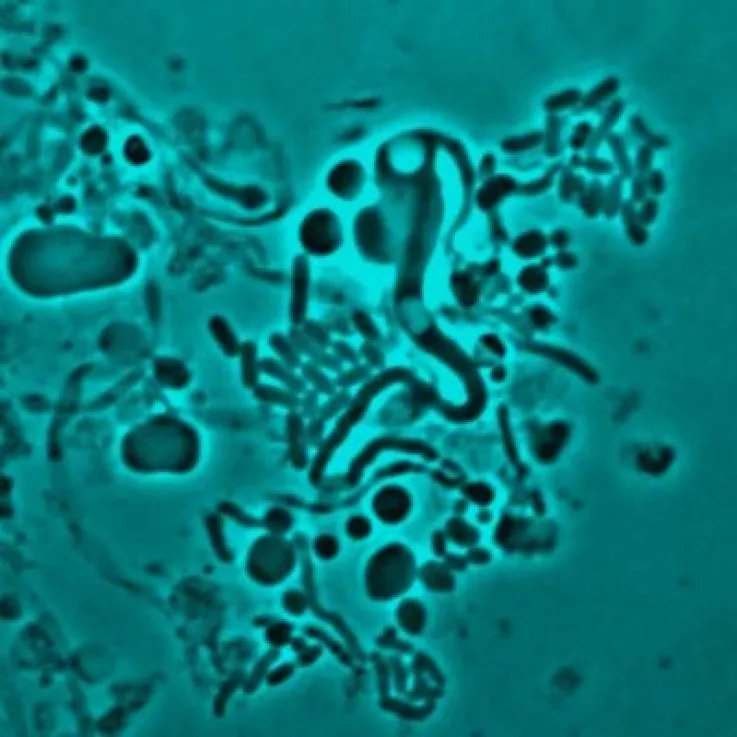

“Imagine that the wall is like the bacteria wearing a high-vis jacket,” explains study lead author Dr. Katarzyna Mickiewicz. “This gives them a regular shape, for example, a rod or a sphere, making them strong and protecting them but also makes them highly visible – particularly to the human immune system and antibiotics like penicillin.” However, once the pathogens shed their walls, they become "invisible" and, therefore, hard to target.

The study, published in Nature Communications on September 26, 2019, focused on the various bacteria associated with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI) in elderly patients. It found that many different bacterial species – including E. coli and Enterococcus – avoid the drugs by resorting to what researchers call "L-form switching." This clever technique, whereby a bacterium sheds its cell wall and takes on an L-shaped form, has been known since the 1930s. However, the pathogens' evasive nature has made it difficult for scientists to study it in detail.

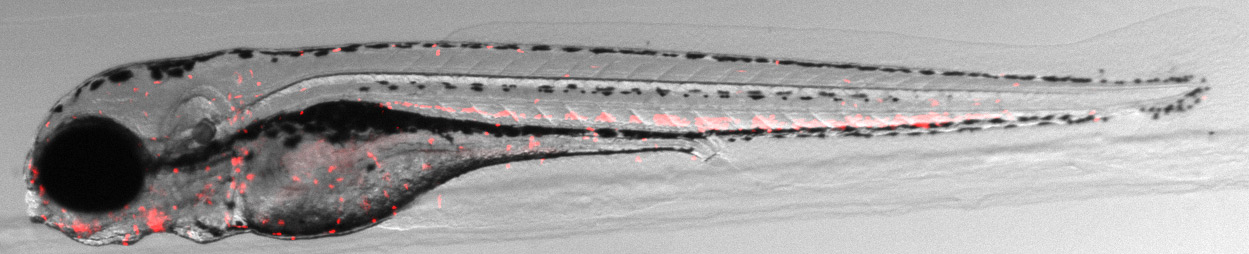

The Newcastle University team successfully detected the sneaky bacteria in action by conducting the experiment in a Petri dish. The scientists observed that the pathogens rapidly began shedding their cell walls when exposed to antibiotics. Once the drugs were removed, the organisms were able to rebuild the protective layer within five hours. Using fluorescent probes, the team was also able to demonstrate the bacteria changing form in a transparent zebrafish embryo where bacteria were able to survive as L-forms once exposed to antibiotics.

Dr. Mickiewicz says: “In a healthy patient this [shedding the cell walls] would probably mean that the L-form bacteria left would be destroyed by their hosts’ immune system. But in a weakened or elderly patient, like in our samples, the L-form bacteria can survive. They can then re-form their cell walls, and the patient is yet again faced with another infection. And this may well be one of the main reasons why we see people with recurring UTIs."

The scientist believes the issue can easily be solved by treating patients with a combination of the usual antibiotics and drugs that kill L-forms. However, detecting the presence of L-shaped bacteria can often be a challenge. “Our battle with bacteria is ongoing. As we come up with new strategies to fight them, they come up with ways to fight back," Dr. Mickiewicz says. "Our study highlights yet another way that bacteria adapt that we’ll need to take into account in our continuing battle with infectious disease."

Resources: Newsweek.com, IFLscience.com, Indepenent.co.uk, NewAtlas.con