Given that even a six month stint at the International Space Station (ISS) causes astronauts to lose bone density and, in some cases, results in visual impairment, researchers have wondered if the human body can withstand a mission to Mars, which could take up to three years. Now, a groundbreaking study involving American twin astronauts Mark and Scott Kelly has found that while the body undergoes drastic changes when exposed to the weightless environment and space radiation for long durations, it mostly reverts to normal upon returning to Earth. This has led the experts to conclude that astronaut health can be "mostly sustained" for a year in space.

The chain of events leading to this critical research began in 2012 after Scott volunteered, and was selected, for a year-long mission to the ISS so NASA scientists could study the impact on his body. Believing the researchers could benefit by comparing the changes with a "control" on Earth, he proposed a "twin study" with his brother Mark, who also happens to be a NASA astronaut. The brothers' identical DNA would make it easy for scientists to determine how the hostile space environment changes the body.

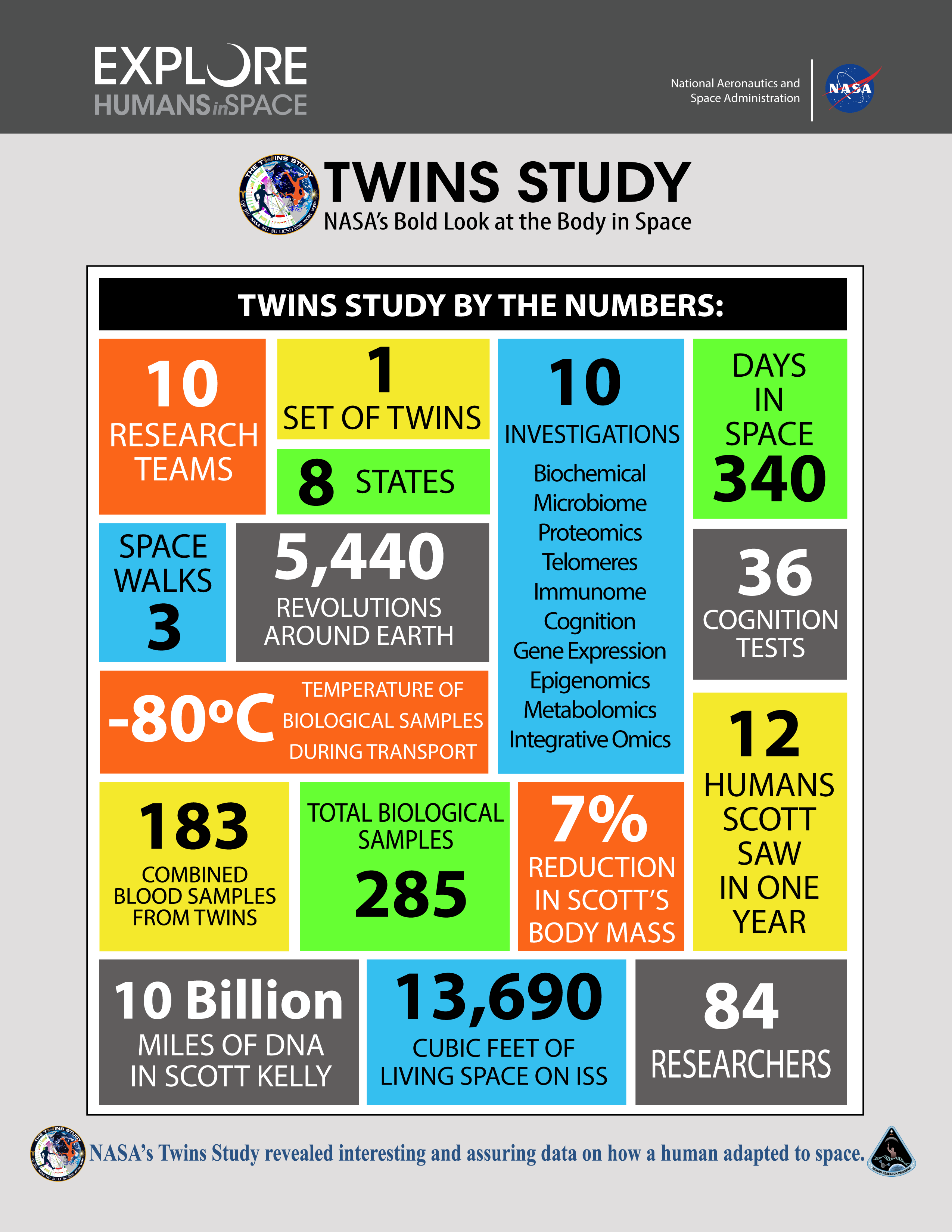

Scott's "Year in Space" mission began on March 27, 2015, when he and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko, who also participated in the year-long experiment, launched to the ISS aboard the Soyuz TMA-16M spacecraft. Throughout his 340 days in orbit, Scott collected blood and urine samples and kept track of the results of the computer games he played to test his cognitive abilities. Mark did the same on Earth.

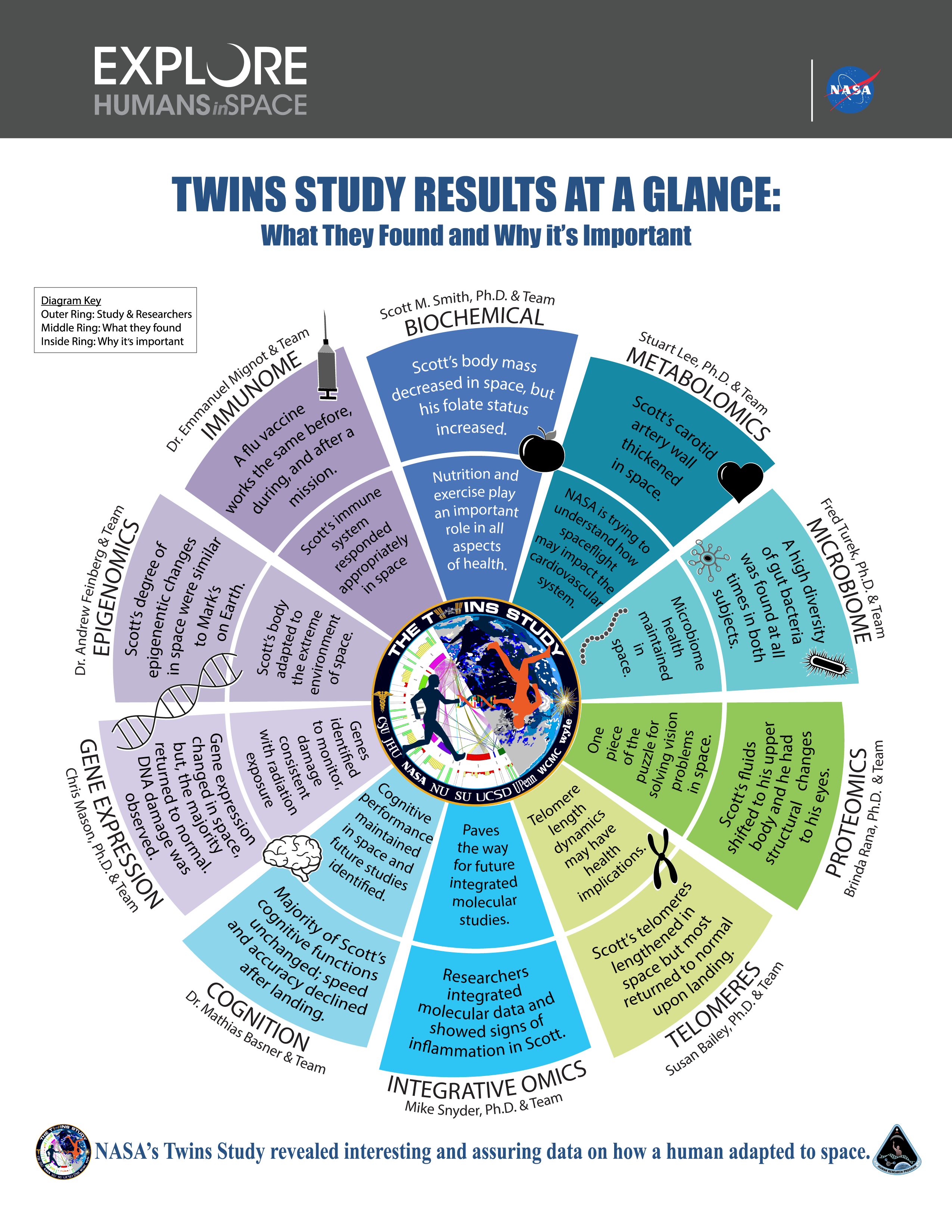

Since Scott's return to Earth on March 2, 2016, 84 scientists from 12 universities have been analyzing the data from his time in space and conducting additional tests on the astronaut. The results, published in the journal Science on April 12, 2019, indicate that the most significant change was observed in Scott's genes, 1100 of which had been drastically altered in space. Some of the changes, related to bone formation and DNA repair, were expected and have been observed in other astronauts as well. Others, like the change in the immune system genes, which help produce energy and protect the body, were new and provide evidence of the stress of long-term spaceflight on the human body.

"Gene expression changed dramatically," said Christopher Mason, one of the study authors and associate professor of physiology and biophysics at Weill Cornell Medicine. "While many of the changes reversed after Scott returned to Earth, a few remained, including cognitive deficits, DNA damage and some changes in T-cell activation. We don't know yet if these changes are good or bad. This could just be how the body responds, but the genes are perturbed, so we want to see why and track them to see for how long."

Another big change was the increase in the length of telomeres — the caps at the end of chromosomes — in Scott's white blood cells. Since telomeres normally shrink when the body is under stress, this was counterintuitive to what the researchers had expected. Though the telomeres have returned to their normal size since the astronaut's return, the scientists wonder if the extended mission will accelerate aging and perhaps even impact Scott's health in the future.

Researchers also observed a difference in the shape of Scott's eyeballs, a thickening of his carotid artery, and a sharp reduction in cognitive speed and accuracy after he returned from space. The good news is that within six months, almost everything had returned to normal!

"He is back to virtually normal," said Dr. Mike Snyder, investigator and director for Stanford University's Department of Genetics. "If you look at the changes that were seen in Scott, the vast majority of them came back to baseline at a relatively short period of time when he returned to Earth, and those that did not return very quickly were markers of things [such as stress and inflammatory] we already knew were likely to happen."

Though the results of the Twin Study are encouraging, NASA needs to conduct additional experiments with other astronauts to determine if all humans react similarly to prolonged exposure to zero gravity and space radiation. To help them, American astronaut Christina Koch — who left for space in March 2019 — plans to remain aboard the ISS until February 2020. Though her 328-day stay is slightly shorter than Scott's 340-day visit, it far surpasses retired NASA astronaut, Peggy Whitson's 288-day record for the longest spaceflight by a female astronaut.

Meanwhile, the Kelly brothers are ready for a second Twins Study, this time with Mark on the ISS and Scott on Earth. "I'd even volunteer to be the person to get to go now that we know this about my brother," Mark said. Scott, on the other hand, is ready to stay among the stars for longer to help the cause. "Put me on a two-year flight," he said to CNN.

While the findings of the studies are crucial for the well-being of astronauts on long-term space missions, they may also be useful for developing new treatments and preventative measures for stress-related health risks on Earth.

Resources: CNN.com. Sciencemag.com,space.com, nasa.gov.