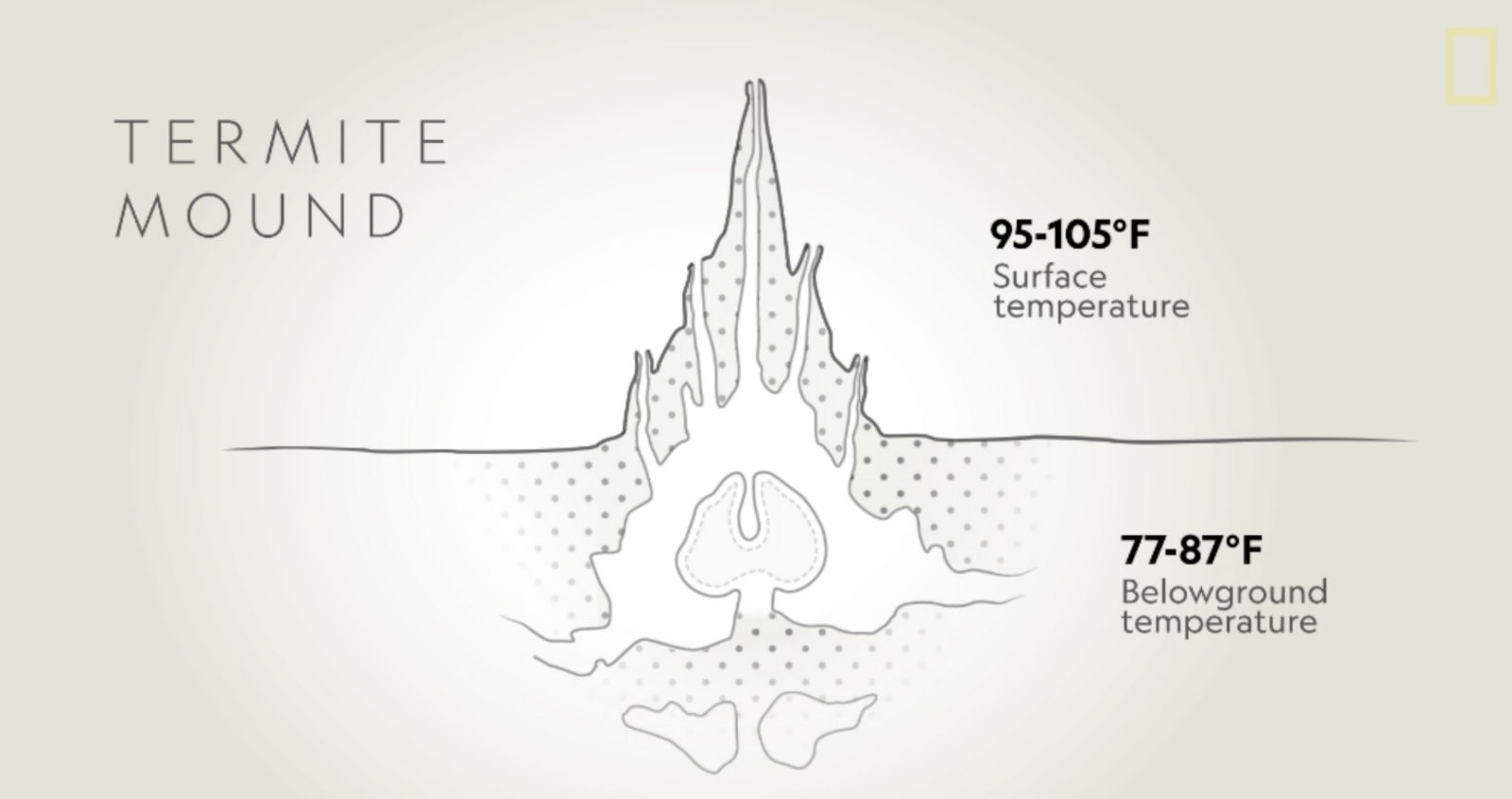

Termites are famous for their superior architectural skills. The mounds created by the industrious insects contain an elaborate network of tunnels with a series of chimneys that help regulate oxygen levels, temperature, and humidity to ensure the queen, who sits in a chamber underneath, is comfortable.

However, the over 200 million mounds, each measuring 30 feet wide at the base and between 6 to 13 feet tall, found in northeastern Brazil are like none other. The structures, big enough to be visible on Google Earth, have neither nests nor chimneys — they are just piles of dirt tossed aside by termites building pathways to forage dead leaves from the forest floor.

Roy Funch of the State University of Feira de Santana in Brazil, who co-authored the study published in Current Biology on November 19, 2018, first noticed the enormous piles of dirt about three decades ago. However, it was just recently, when farmers began clearing the semi-arid forests to free up more land for farming and grazing, that scientists realized the large structures occupy an area the size of the US state of Oregon! Curious to find out more about the "biological wonders," Funch teamed up with Stephen Martin of the University of Salford in the United Kingdom.

A cross-sectional examination of the cones, or murundas as they are called in Brazil, revealed that unlike other termite mounds, the tube is closed at the top and does not provide ventilation. "They’re just amorphous lumps of soil, with no internal structures. Nothing lives inside them," says Funch. He believes the large number of mounds are a byproduct of the area's dry ecosystem. To find enough leaves to forage, the termites have to constantly expand their network of tunnels. The soil tossed out while creating these pathways builds up over time, resulting in massive cones across a large span of the surface.

To investigate how long the massive structures have been hiding in plain sight, the researchers collected samples of soil from the center of 11 mounds. Their analysis indicated that the youngest muranda was about 690 years old, while the oldest dated back an astonishing 3,890 years — about the same as the world's oldest-known termite mound found in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Africa.

Funch and Martin initially suspected the mounds were the work of several competing termite species. However, as it turned out, they are all created by the Syntermes dirus (S. dirus) termites. "These mounds were formed by a single termite species that excavated a massive network of tunnels to allow them to access dead leaves to eat safely and directly from the forest floor," says Martin. "The amount of soil excavated is over 10 cubic kilometers, equivalent to 4,000 great pyramids of Giza, and represents one of the biggest structures built by a single insect species."

The one thing the researchers are unsure about is if the tunnels are abandoned once the termite colony that created them dies, or if they are used by future generations, who continue to dig additional pathways, adding to the giant heaps of soil. They also need to investigate how the termite colonies are structured, given that they have been unable to find a queen chamber of the species inside any of the mounds.

Resources: TheAtlantic.com, sciencedaily.com, livescience.com,cnn.com