In most democratic countries, all voters go to the polls on a single, predetermined day. However, this is not the case in India, the world's largest democracy and the planet's second most populous country after China. In this diverse subcontinent — which boasts 22 official languages, 200 regional languages, and over 6000 dialects across its 29 states and 7 Union territories — voting is an elaborate process, conducted in seven stages over a period of 39 days. Held every five years, this year the general elections began on April 11, 2019 and will continue until May 19, 2019, with the final results announced on May 23, 2019.

What is at stake?

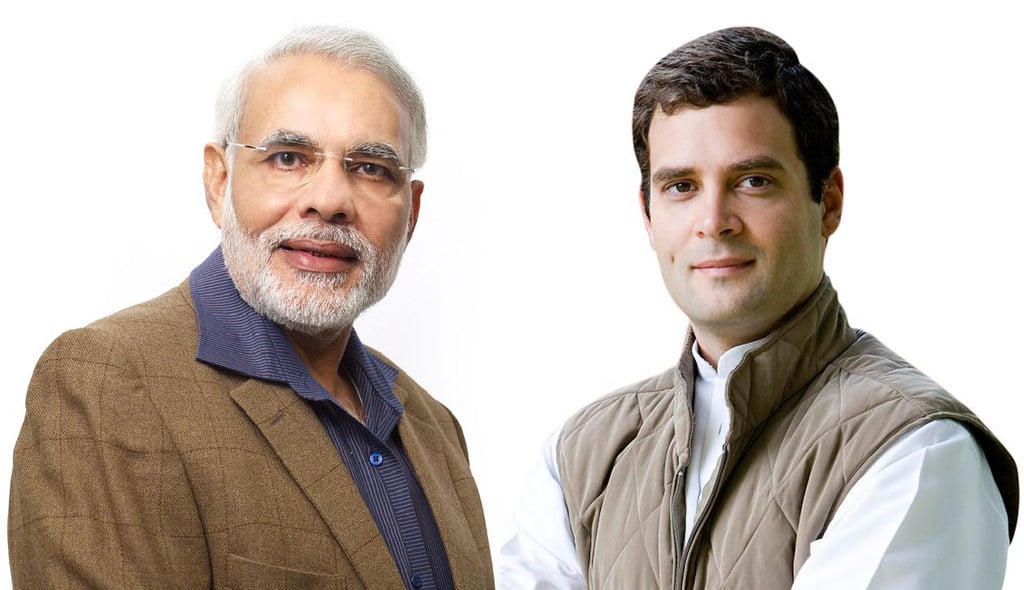

The general elections allow residents to select their representative for the lower house of parliament — the Lok Sabha, or House of the People — which comprises 545 members, 543 of which are chosen by constituents. The party that garners the majority of the seats, in this case, 272, can select their leader to be the country's prime minister for the next five years. Political parties can also band together to form a coalition government if there is no clear front-runner. While similar rules apply in other democratic countries, what makes India's election process more complex is that there are currently over 8,000 political aspirants representing 2,354 different parties who could potentially get elected. While candidates of the two largest — the Bharatiya Janata Party, led by current prime minister Narendra Modi, who is seeking a second term, and the Indian National Congress, led by Rahul Gandhi — are likely to get many of the votes, neither are expected to win the 272 seats needed to form a single-party government.

Why are the elections staggered over five weeks?

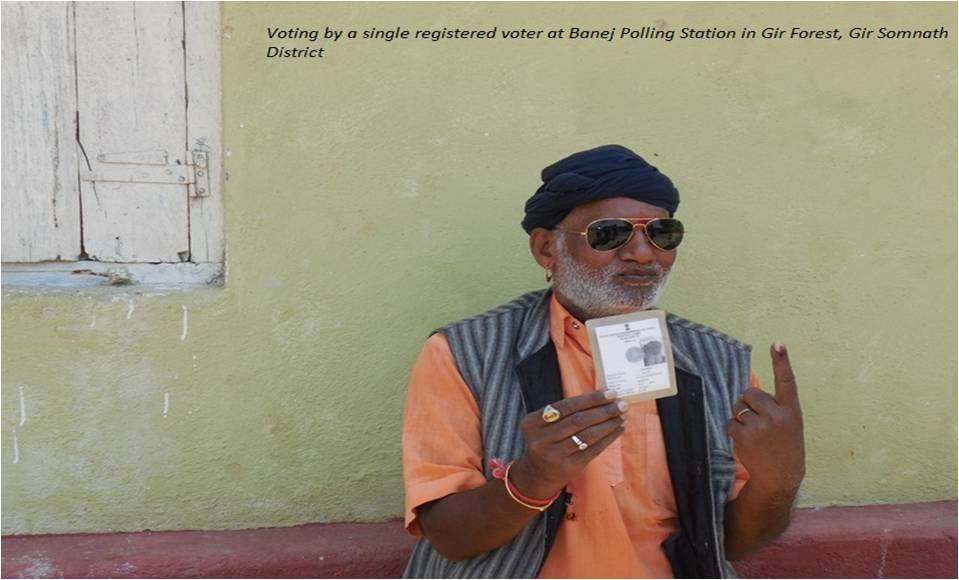

While holding elections in several stages over a period of five weeks may sound excessive, it is the only way poll workers can get to the 900 million eligible voters who reside all the way from the Himalayas to the tropical islands in the Indian Ocean. What makes the exercise even more complicated is the electoral rules which stipulate that no voter should be more than 1.2 miles (2-kilometers) away from a polling booth. This year, election organizers have set up 1 million stations, installed 2.3 million electronic voting machines, and deployed 10 million government employees — who travel by foot, road, train, helicopter, boat, and sometimes even elephant — to ensure that every voter can cast a ballot. They even set up a special polling booth for Guru Bharatdas Darshandas, the sole resident and caretaker of the Gir Forest, home to India's only wild lion population.

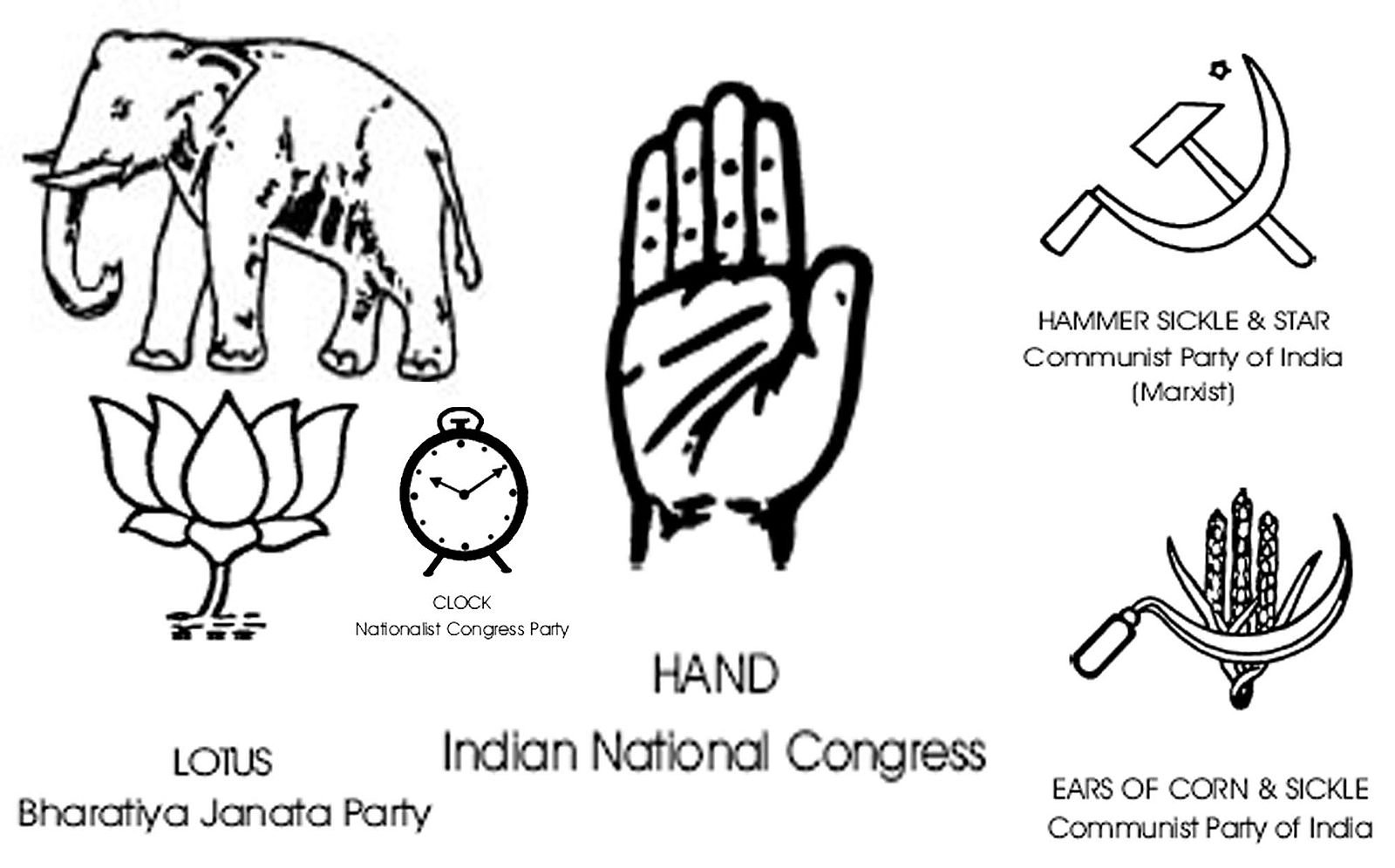

What's with the emoji-like symbols on the electronic ballots?

India's electronic voting ballots feature emoji-like symbols alongside each candidate's name. The minimalist drawings, which include everyday objects, such as a broom, belt, flashlight, and even mango, are images selected by the various political parties to differentiate themselves and make it easier for voters to choose between candidates. The icons were introduced at India's first election in 1951 to help the country's population, which was about 80 percent illiterate, recognize who they were voting for. "Symbols made it easier for people to associate [themselves] with political parties. They are like the logos of companies," said Kavita Karan, a professor at Southern Illinois University. Though the country's literacy rate has risen sharply since, the drawings remain an essential part of the election process, appearing prominently on political banners as well as on documents released by parties to make their case to voters.

Political parties, however, do not get to design their own logos. Instead, they can select three symbols, in order of choice, from a general pool of images maintained by the Election Commission of India (ECI). Once a logo has been allocated, it cannot be given to anyone else, even if the political party it represents ceases to exist. This means new entrants have to select from the list of the ever-dwindling "free" symbols that remain.

How much does the election extravaganza cost?

Not surprisingly, elections in the world's largest democracy are an expensive affair. This year's polling exercise is expected to cost a record $7 billion, up 40 percent from the estimated $5 billion spent by candidates in the 2014 elections. While most of the funds will go towards social media, travel, and advertising, candidates also spend large amounts to win over residents. To attract large crowds to rural political rallies, they often treat prospective voters to delicious biryani — a fragrant, spiced rice mixed with vegetables or chicken — firework shows, and dance performances. Rural voters are also often bribed with cash and gold, as well as simple household items like blenders, refrigerators, and even goats! While India's secret ballot system makes it hard to gauge the effectiveness of the illegal presents, more than 90 percent of candidates have confessed to using them to stand out in the crowded field. Hopefully, Indians will vote in leaders who are good for the country, not those that hand out the best gifts!

Resources: NPR.org, abc.net.au, wikipedia.org,carnegieendowment.org