Cotton candy is probably the last thing that comes to mind when one thinks of exoplanets. But the three giant worlds orbiting the Kepler 51 star system, about 2,600 light-years away from Earth, are so "light and fluffy" that they warrant a comparison to the beloved spun-sugar confection.

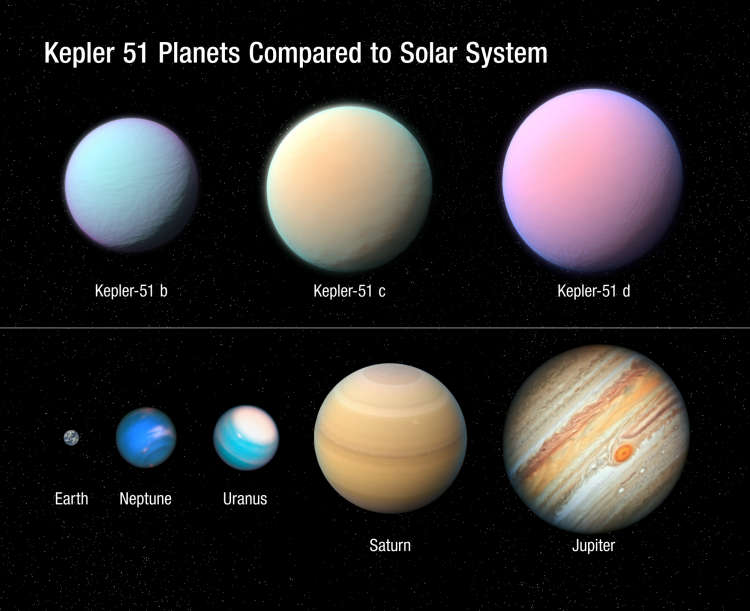

The exoplanets named Kepler 51 - b, c, and d, detected by NASA's Kepler Space Telescope between 2012 and 2014, belong to a rare class of low-density "super-puffs" — only 15 of which are known to exist. Curious about the composition of the exoplanets’ atmospheres and to find clues around how these lightweight worlds may have formed, a team led by the University of Colorado (CU), graduate student, Jessica Libby-Roberts, decided to investigate.

The scientists began by using the Hubble Space Telescope to zoom in on the 500-million-year-old Kepler 51-star system, which hosts the planets. The data enabled the team to develop accurate estimates for the three planets' masses and densities. The researchers' calculations revealed the three "super-puffs" had a density of less than 0.1 g/cm³ of volume — almost identical to that of the sweet pink carnival treat. In contrast, the similar-sized Jupiter boasts a density of 1.33 g/cm³. “We knew they were low density,” said Libby-Roberts. “But when you picture a Jupiter-sized ball of cotton candy—that’s really low density.”

While confirming the planets' "super puff" status was easy, using the Hubble to peer into their atmosphere proved impossible due to a high-altitude opaque shell around each of their outer layers. “This was completely unexpected. We had planned on observing large water absorption features, but they just weren’t there. We were clouded out,” Libby-Roberts said.

Computer simulations and other tools led the researchers to theorize that the Kepler-51 planets most likely comprise lightweight gases like hydrogen and helium, which also explains their puffiness. They suspect that similar to Saturn's moon Titan, the worlds are encompassed by a layer of methane. “If you hit methane with ultraviolet light, it will form a haze,” Libby-Roberts said. “It’s Titan in a nutshell.”

Libby-Roberts and study co-author, CU assistant professor Zachory Berta-Thompson, maintain that the "super-puff" worlds may not be as unusual as was first thought. Their observations showed the trio were shedding as much as tens of billions of tons of gas into space every second. The researchers say if the pace continues, the planets will lose their cotton-candy puffiness within the next billion years and end up looking more like the normal class of exoplanets called “mini-Neptunes.”

“People have been really struggling to find out why this system looks so different than every other system,” Libby-Roberts said. “We’re trying to show that, actually, it does look like some of these other systems.” Berta-Thompson agreed: “A good bit of their weirdness is coming from the fact that we’re seeing them at a time in their development where we’ve rarely gotten the chance to observe planets.”

Only time will tell if the scientists are right. For now, it is just fun to imagine three ginormous balls of cotton candy floating around in our universe.

Resources: www.colorado.edu, NASA.gov