Over the years, researchers have unearthed fossils of many of the estimated 2,468 dinosaur species that roamed Earth during the Mesozoic era, which spanned from between 252 million years ago to about 66 million years ago. However, few can compare to the discovery of Oculudentavis khaungraae, the smallest dinosaur ever known to live on the planet.

"This discovery is a stark reminder that ancient birds, and even non-bird dinosaurs potentially, may have evolved to diminutive sizes, but are unknown because they are too small to preserve in the fossil record under ordinary circumstances," Darla Zelenitsky, an assistant professor of dinosaur paleobiology at the University of Calgary, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

O. khaungraae's skull, perfectly preserved inside a 1.5-inch wide piece of amber, that is 99 million years old, was discovered in a northern Myanmar mine in 2016 and donated to China's Hupoge Amber Museum. Its significance came to light recently after Lida Xing, an associate professor at the China University of Geosciences who co-led the study, shared images of the birdlike fossil head with Jingmai O'Connor, a senior professor of vertebrate paleontology at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

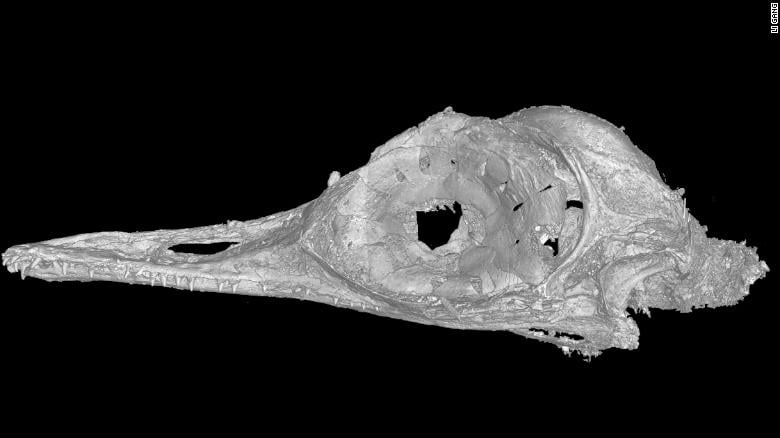

High-resolution CT scans revealed that the entire fossil, including the beak, was a mere 0.56 inches (14.1 millimeters) in length. This led the paleontologists to estimate that the dinosaur was smaller than the world's smallest bird - the 2.25-inch-long (57.15-millimeter) long bee hummingbird — and weighed about 0.07 ounces (2 grams). Roger Benson, a professor of paleobiology at the University of Oxford, believes that at one-sixth the size of the smallest known early bird fossil, O. khaungraae was also the smallest-known dinosaur of the Mesozoic era.

Small as it may have been, the animal, which was armed with more than 100 sharp teeth, was probably a fierce predator. "It has more teeth than any other Mesozoic bird that we know of," said O'Connor. It even had teeth in the back of its jaw, under its eye, "which suggests that the animal could really open its mouth really, really wide." she added. However, given its size, the dinosaur posed little danger to most creatures. "Since it's so tiny, we envision the only thing it was possibly able to feed on was insects, and other invertebrates," O'Connor told Live Science.

The researchers, who published their findings in the journal Nature on March 11, 2020, state that the dinosaur's diminutive size may be the result of living at a time when that part of Myanmar was on an island arc. A theory on animal size suggests that larger creatures "miniaturize" when they evolve on isolated islands like the Myanmar region was during ancient times. Not surprisingly, animals undergoing the process of miniaturization face numerous challenges, including fitting all their sensory organs into a tiny head.

O. khaungraae's skull had several unusual features not encountered before in Mesozoic era dinosaur or bird fossils. It had small pupils, indicating that it preyed during daylight hours. Its bulgy eyes were located on the side of its tiny face suggesting that the dinosaur did not possess the binocular vision required for the depth perception that is commonly found in predatory birds. Instead of the ring of bones that support birds' eyes, the avian dinosaur had spoon-shaped bones similar to those found in lizards. "It's the weirdest fossil I've ever been lucky enough to study," said O'Connor. "I just love how natural selection ends up producing such bizarre forms."

The scientists say not having the dinosaur's entire skeleton makes it hard to determine precisely how O. khaungraae is related to other birdlike dinosaurs. However, they suspect it belonged to a group of relatively primitive birds that lived between 150 million and 120 million years ago.

Though the team has been able to uncover invaluable information about the tiny dinosaur, O'Conner is not satisfied. She says, "This paper is just scratching the surface of the information preserved. Is the skull petrified, or is it the original material unaltered, preserved in the amber? Mummified, if you will? What color was it, and can we use isotopes to figure out exactly what it ate; can we reconstruct the brain better?" Unfortunately, the researcher admits those answers will have to wait until new methods for extracting data from amber in a non-destructive manner have been developed.

Resources: www.livescience.com, sciencemag.org, mentalfloss.com