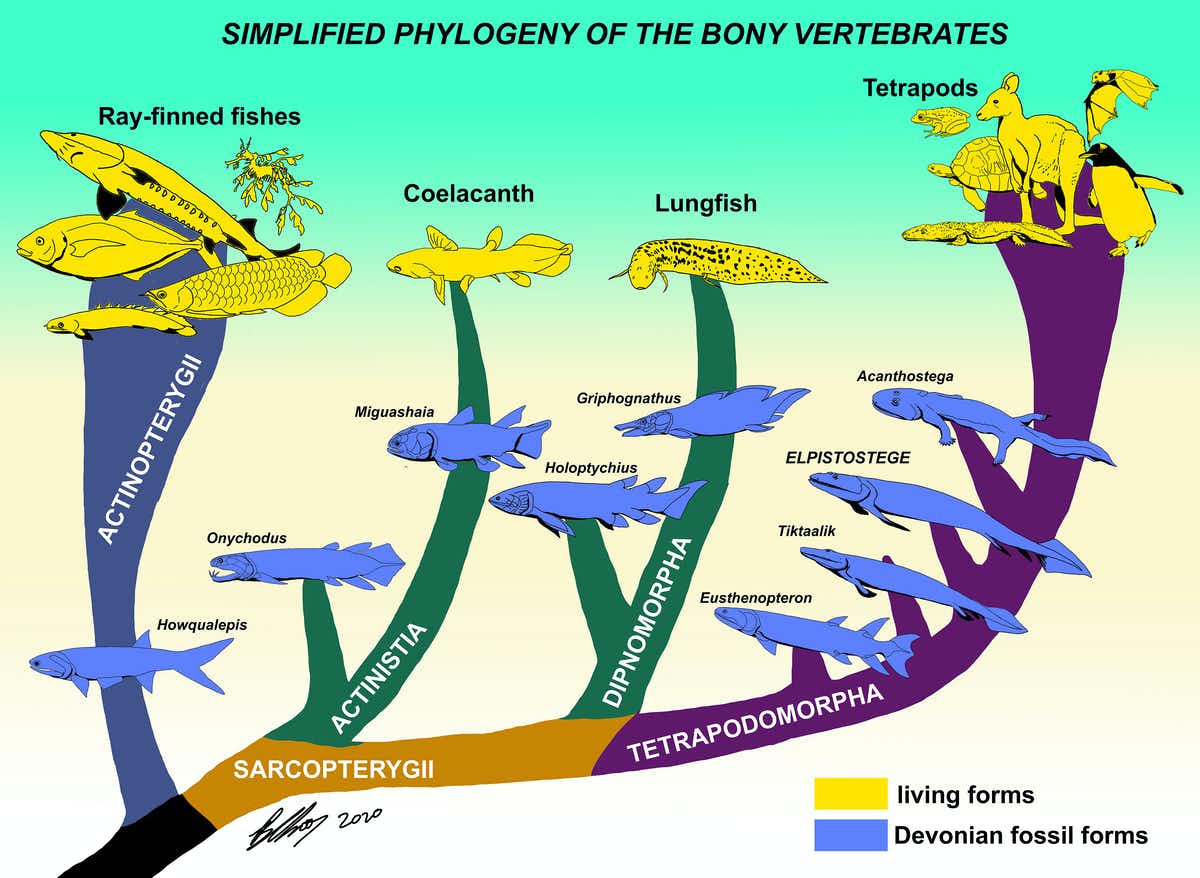

Researchers have long believed that all four-limbed animals or tetrapods, a group that includes amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, evolved from an ancient group of fish known as Elpistostege watsoni, which lived between 416 million and 358 million years ago, during the Devonian Period.

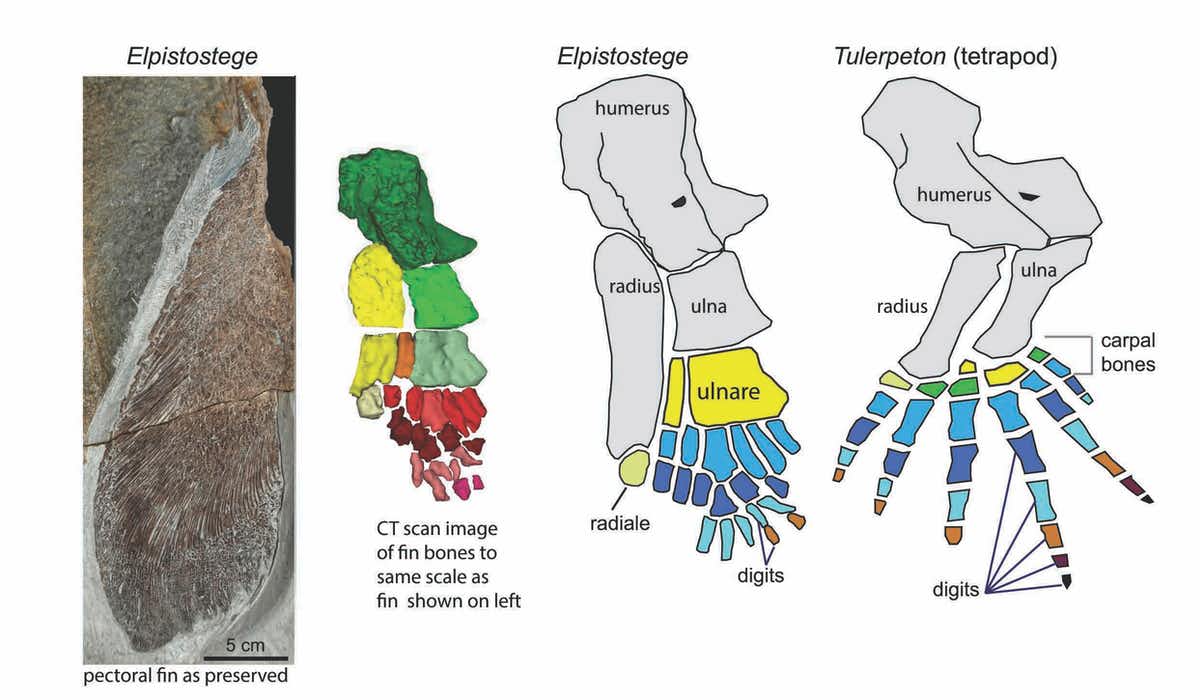

Over the years, partial remains of the creatures, which possessed characteristics of both lobe-finned fishes and tetrapods, has shed light on some of the anatomical change the creatures underwent, such as breathing, hearing, and feeding. However, the lack of a complete pectoral fin fossil had made it impossible to determine the evolution of one of the most important features for the transition — hands!

Now, thanks to the pristinely-preserved remains of a 5-foot (1.57 meter) long E. watsoni specimen, scientists finally have some evidence. The 'missing link' was discovered in Miguasha National Park in Quebec, Canada, a treasure trove of animal fossils from the Devonian Period, in 2010. However, it was only recently that an international team of paleontologists from Flinders University in Adelaide, Australia, and Canada's Quebec University studied the remains in detail.

The examination revealed that the crocodile-like creature, which lived in the shallow waters of an ancient estuary, had a flat head, long snout, and small round eyes. But it was the well-preserved pectoral fins that fascinated the scientists. Revealing the presence of phalanges, or phalanx bones, organized in digits (fingers), it provided the first evidence of finger-like bones that eventually evolved into hands. The discovery, published in the journal Nature on March 18, 2020, suggests that fingers in vertebrates originated in fish, rather than in later land dwellers

Study co-author Professor John Long, a paleontologist at Flinders University, says, "We believe this is the first evidence of digit bones found in a fish fin with fin-rays [the bony rays that support the fin]. This suggests the fingers of vertebrates, including human hands, first evolved as rows of digit bones in the fins of Elpistostege fishes."

to tetrapods, a group that includes humans (Credit: Brian Choo/CC-BY-SA 2.0/The Conversation)

Quebec University 's Richard Cloutier, who led the research, believes the evolution to digits most likely began when the fish was starting to support its own weight in shallow water or on land. He says, "The increased number of small bones in the fin allows more planes of flexibility to spread out its weight through the fin." The researcher asserts the E. watsoni may not necessarily be our ancestor, "But it is the closest we can get to a true 'transitional fossil,' an intermediate between fishes and tetrapods."

Resources: theconversation.com, dailymail.co.uk