Male birds typically sing the same tunes as the rest of their species because an unrecognizable song defeats the two primary reasons for their crooning — to establish and defend their territory and to attract mates. While the songs, which are passed down from generation to generation, may vary slightly by region, any new compositions are typically limited to the local environment. However, for reasons unknown to scientists, white-throated sparrows across Canada are abandoning their classic song for a catchy new tune "written" by their peers in British Columbia.

"As far as we know, it's unprecedented. We don't know of any other study that has ever seen this sort of spread through cultural evolution of a song type," says biologist and study lead author Dr. Ken Otter from the University of Northern British Columbia (UNBC).

The new song was first brought to Otter's attention in the 1990s by Dr. Scott Ramsay, an associate professor at Wilfrid Laurier University. The two were birdwatching outside UNBC's Prince George campus when Ramsay said, "Your sparrows sound weird."

Upon listening carefully, the bird behavior and communication expert realized Ramsay was right. "White-throated sparrows have this classic song that's supposed to sound like it goes, 'Oh, sweet Canada, Canada, Canada,'" Otter wrote in an e-mail to Forbes. "And our birds sound like they're going, 'Oh, sweet Cana– Cana– Cana– Canada.'"

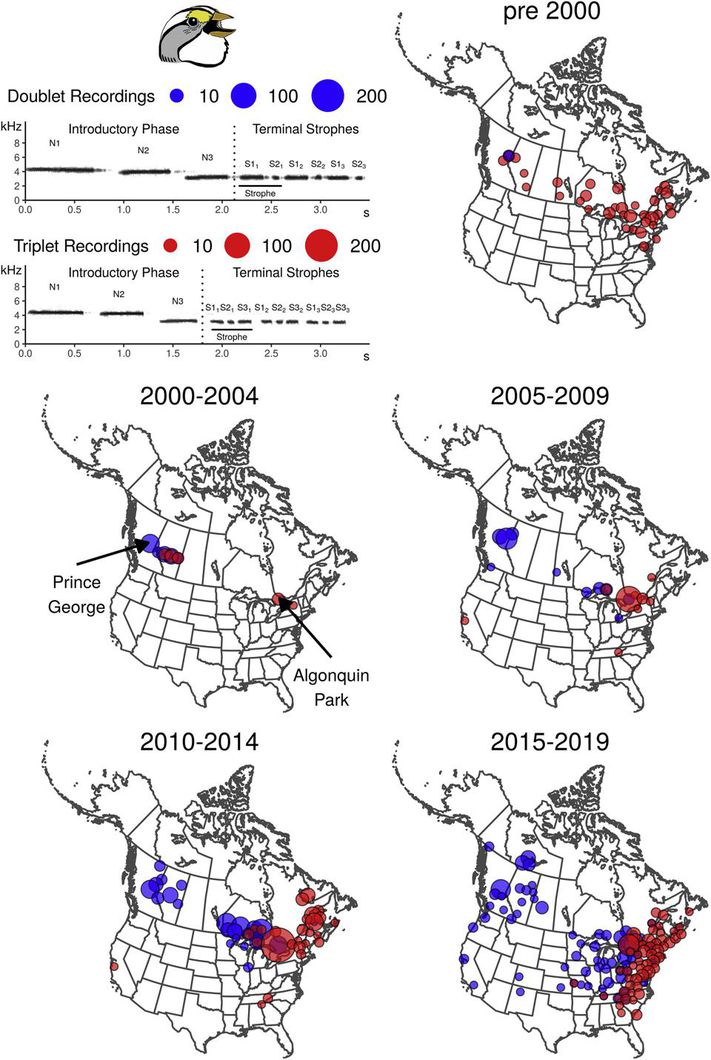

Otter and Ramsay initially dismissed the variation as a new dialect that had been reinforced by local learning. However, upon finding out that white-throated sparrows east of Prince George had also adopted the shortened version, they decided to investigate further. An analysis of 1800 bird songs recorded and downloaded by citizen scientists between 2000 and 2019 revealed that sparrows across the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Ontario, and even western Quebec were singing the new song.

"Originally, we measured the dialect boundaries in 2004, and it stopped about halfway through Alberta," Otter said. "By 2014, every bird we recorded in Alberta was singing this western dialect, and we started to see it appearing in populations as far away as Ontario, which is 1,864 miles (3,000 kilometers) from us."

Since bird songs are learned and not inherited, the researchers wondered if it could have been spread by eastern sparrows intermingling with western sparrows during winter. To verify if the two groups do spend winters together, Otter's team attached geolocators on 50 wild Prince George sparrows. Sure enough, the birds all flocked to the same wintering grounds.

"We know that birds sing on the wintering grounds, so juvenile males may be able to pick up new song types if they overwinter with birds from other dialect areas. This would allow males to learn new song types in the winter and take them to new locations when they return to breeding grounds, helping explain how the song type could spread," Otter explains.

The scientists, who published their findings in the journal Current Biology on July 2, 2020, are not sure why the new song has gone viral. Experiments the team conducted indicate that the song's use did not result in any territorial advantage, leading them to suspect it may be favored by females. Emily Hudson, a biologist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville who wasn't involved in the research, wonders if the new song may also be easier to learn, making it more popular with the young males.

"In many previous studies, the females tend to prefer whatever the local song type is," says Otter. "But in white-throated sparrows, we might find a situation in which the females actually like songs that aren't typical in their environment. If that's the case, there's a big advantage to any male who can sing a new song type."

While the world is just becoming aware of the tune change, Prince George's white-throated sparrows have already moved on and are now belting out a new version of the doublet-ending song. Otter and his team plan to track the new song's spread with help from citizen scientists. "By having all these people contribute their private recordings that they just make when they go bird watching, it's giving us a much more complete picture of what's going on throughout the continent," he says. "It's allowing us to do research that was never possible before."

Resources: www.audubon.org, gizmodo.com, scitechdaily.com,