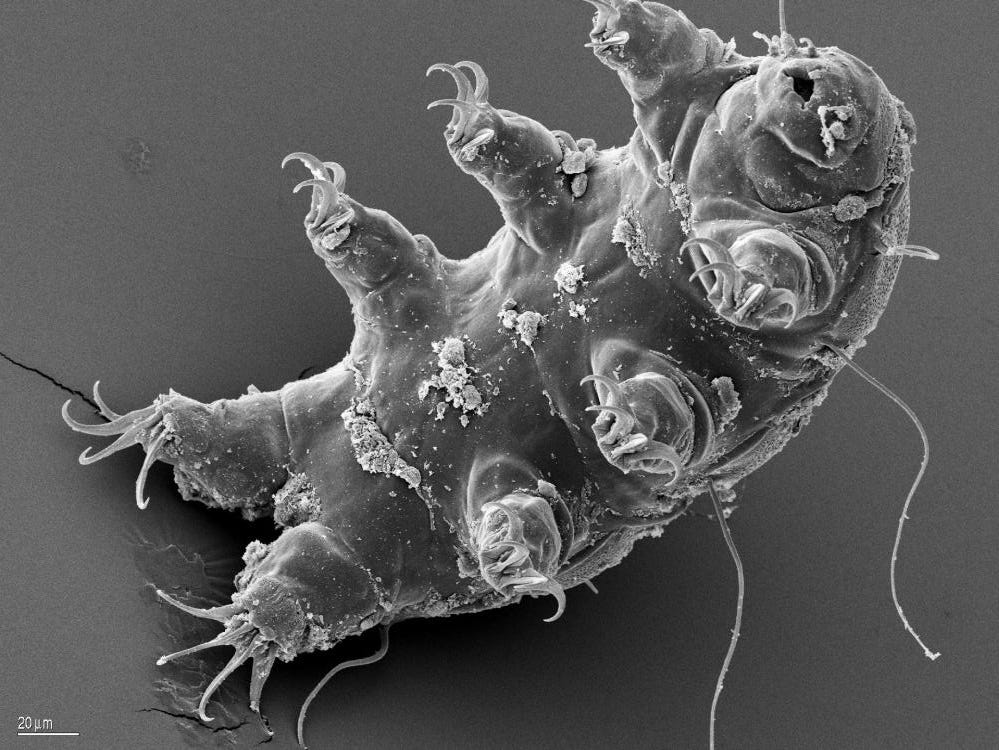

Tardigrades, or water bears, are virtually indestructible. The eight-legged microscopic animals can withstand extreme temperatures, survive without food for decades, and even exist in a vacuum in space. But, despite being around for over 500 million years, they rarely appear on the fossil record. Their miniature size and lack of hard tissue make it hard for them to fossilize. Even when they do get preserved, the tiny creatures are hard to spot and often get overlooked. Over the years, only two tardigrade fossils have been found. Now, a third specimen — one of a new tardigrade species — has joined this exclusive group.

"The discovery of a fossil tardigrade is truly a once-in-a-generation event," Phil Barden, co-author of the October 6, 2021, study published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, said in a press release. "What is so remarkable is that tardigrades are a ubiquitous ancient lineage that has seen it all on Earth, from the fall of the dinosaurs to the rise of terrestrial colonization of plants. Yet, they are like a ghost lineage for paleontologists, with almost no fossil record."

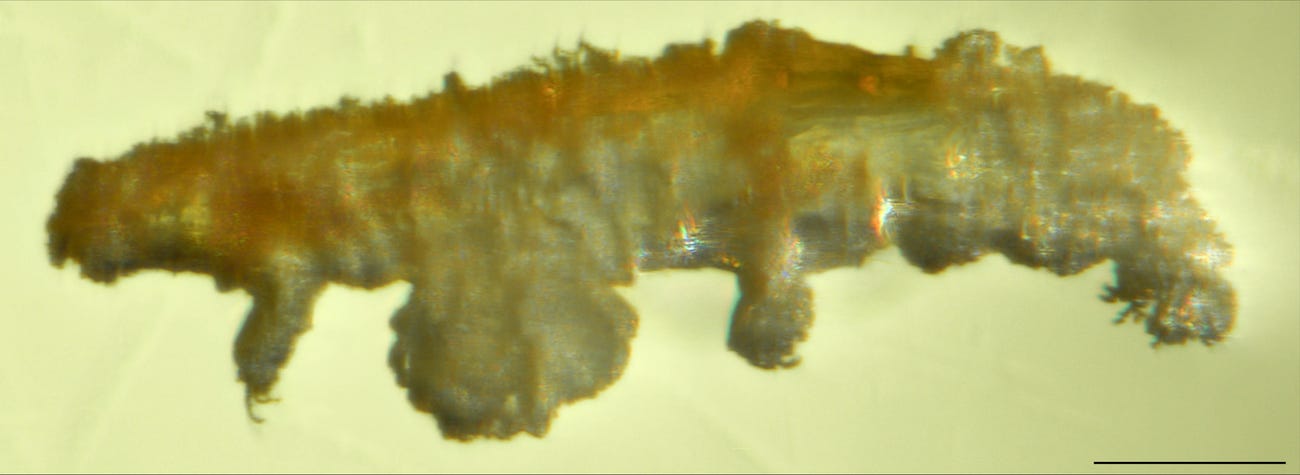

The 16 million-year-old specimen, found encased in amber in the Dominican Republic, is the first of its kind from the Cenozoic period — Earth's current geological era, which began 66 million years ago. The previous fossils found — one in 1964 and the other in 2001 — date back 78 million years and 92 million years, respectively.

Even better, the specimen's proximity to the amber's surface allowed Barden and his team at the New Jersey Institute of Technology to examine the ancient tardigrade's mouth and claws. They were also able to reconstruct what its throat and guts looked like. The team called the new species Paradoryphoribius chronocaribbeus. "Chrono" means time in Greek, while "caribbeus" is a nod to the area of the Dominican Republic where the fossil was found.

The researchers say the find was extremely fortunate, especially since Barden had initially picked up the amber to examine the ants and beetles trapped inside. It was only after an observant lab member noticed the tardigrade's almost invisible, 0.6-millimeter-long torso alongside the insects, that they turned their focus away from the bugs. "It was more luck that they saw it … because it's not something they look for," said study leader Marc Mapalo. The doctoral candidate at Harvard University believes fossils like these will enable paleontologists to better understand how these creatures evolved and survived Earth's five major mass extinction events.

Resources: Livescience.com, Businessinsider.com, NPR.com