Though it is not unusual to find marine animals thriving under the Antarctica seafloor, researchers had always assumed that all life would become less abundant farther away from open water and sunlight. However, the discovery of filter-feeding organisms — 160 miles (260 km) away from the open ocean, with temperatures of −2.2°C and under complete darkness — suggests that life in the world's harshest environment may be more adaptable and diverse than previously thought.

“It’s slightly bonkers,” says British Antarctic Survey (BAS) marine biogeographer and study leader Dr. Huw Griffiths. “Never in a million years would we have thought about looking for this kind of life because we didn’t think it would be there.”

In 2017, BAS geologist James Smith and his colleagues embarked on a three-month expedition to the middle of Antarctica's Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf, to retrieve a sample of the seafloor sediment. The team drilled through the half-mile of ice by pumping almost 20,000 liters of hot water — created by melting 20 tons of snow — through a pipe lowered down a borehole. After about 20 hours of painstaking work, they were finally able to pierce through the ice shelf and reach the seabed underneath.

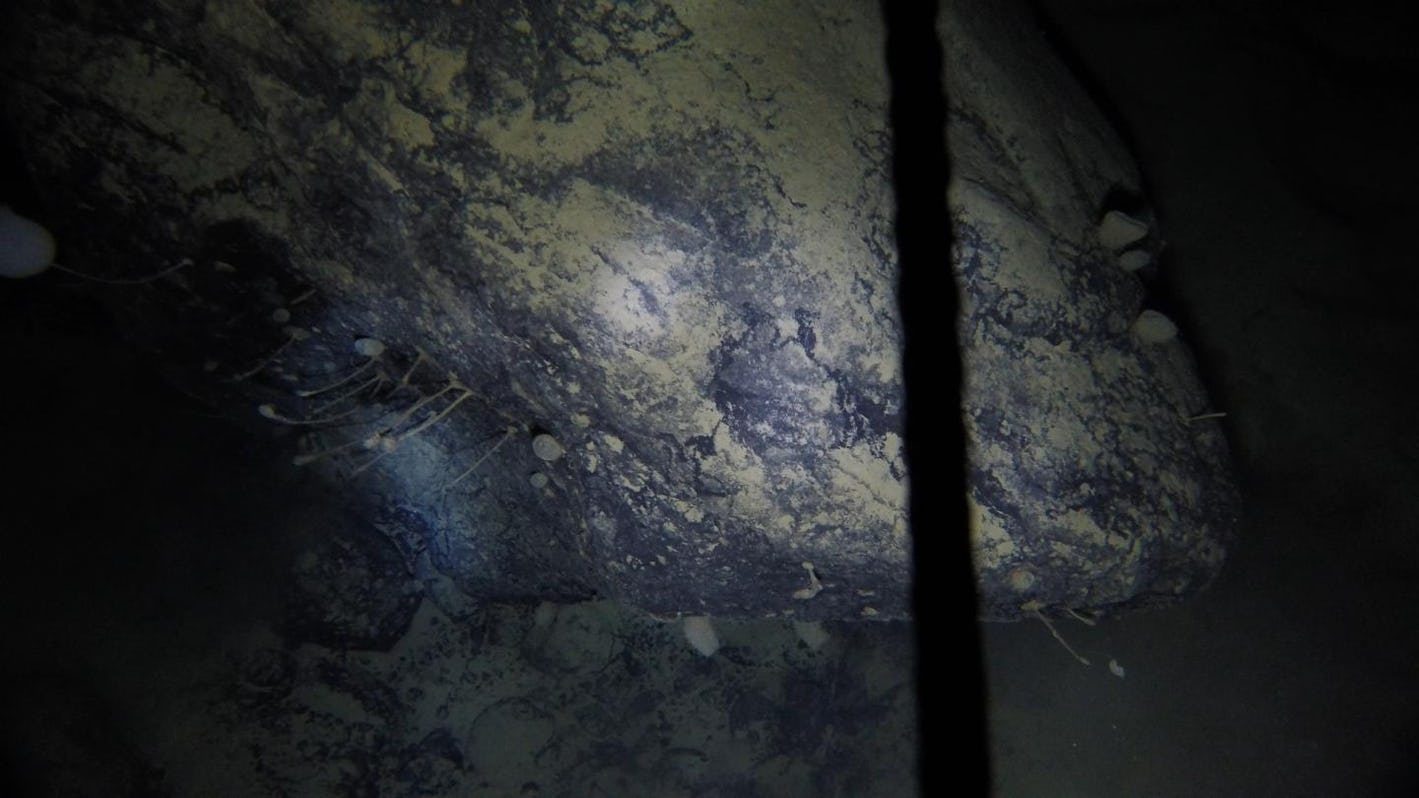

However, when the scientists lowered the instrument, along with a GoPro camera, to retrieve a soil sample, it came up empty. After multiple failed tries — each round trip taking about an hour — the researchers took a closer look at the footage and noticed a massive boulder sitting amid the relatively flat seabed. Even more surprising, the rock was covered with stationary animals, like sponges and potentially several previously unknown species.

The finding was particularly confounding given that sessile organisms — such as sponges and coral polyps — which spend their entire lives attached to submerged rocks, or other hard surfaces, need a constant food supply. In the open water, the "marine snow," as it is called, comes from decaying organic matter, which drifts down from the upper waters to the deep ocean. However, the organisms attached to the ice-shelf boulder are too far from the open sea to receive a steady supply of nutrients. To make matters worse, due to the area's strong ocean currents, the food has to travel anywhere from 370 to 930 miles to get to them.

“This is by far the furthest under an ice shelf that we’ve seen any of these filter-feeding animals,” said Griffiths. “These things are stuck on a rock and only get fed if something comes floating along."

The scientists, who published their findings in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science on February 15, 2021, say that since they cannot collect samples, it is difficult to get more insights into the organisms. “It was a real shock to find them there, a really good shock, but we can’t do DNA tests, we can’t work out what they’ve been eating, or how old they are. We don’t even know if they are new species, but they’re definitely living in a place where we wouldn’t expect them to be living,” Griffiths said.

Resources: Livescience.com, newscientist.com, bas,ac.uk