Jerome Mallefet/National Fund for Scientific Research, Catholic University of Louvain)

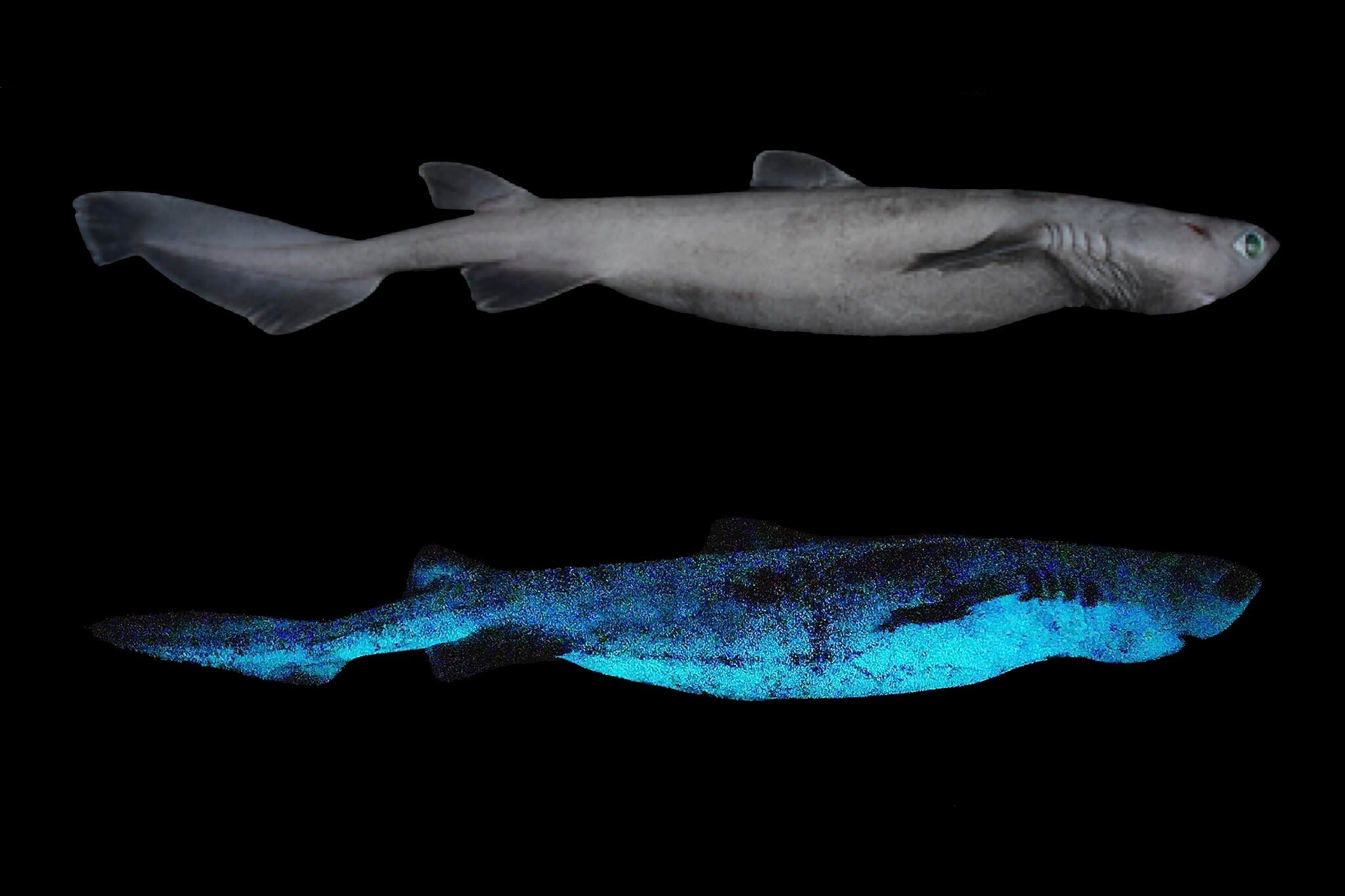

While bioluminescence — the ability to glow in the dark — is a fairly common occurrence in fish and squid that live in the ocean's darkest depths, its presence in sharks is not as well-documented or understood. Now, the discovery of the largest-known luminous vertebrate — the six-foot-long kitefin shark — and two other glowing shark species has enabled researchers to gain valuable insights into the luminescent abilities of the deep-sea creatures.

“We have something like 540 shark species in the ocean [and] there are 57 of them able to produce light — so more than 10% of the sharks,” Jérôme Mallefet, a marine biologist at the Catholic University of Louvain in Belgium and lead author of a new study, published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science on February 26, 2021, told Mongabay. “But do people know they are able to produce light? No, not much.”

The kitefin shark's hitherto unknown talent was discovered in January 2020, during a month-long expedition conducted by New Zealand researchers. They were documenting the population of a white-fleshed fish, called Hoki, in the waters off the country's East Coast. Each time the scientists drew up fish from depths as far down as 2,600 feet, Dr. Mallefet and his team — who had joined the annual survey to conduct their own research — would quickly scan the net for sharks. Since sharks have no swim bladders and can survive the drastic pressure change, they were able to transfer a few live specimens into tanks situated inside a dark, cold room for observation.

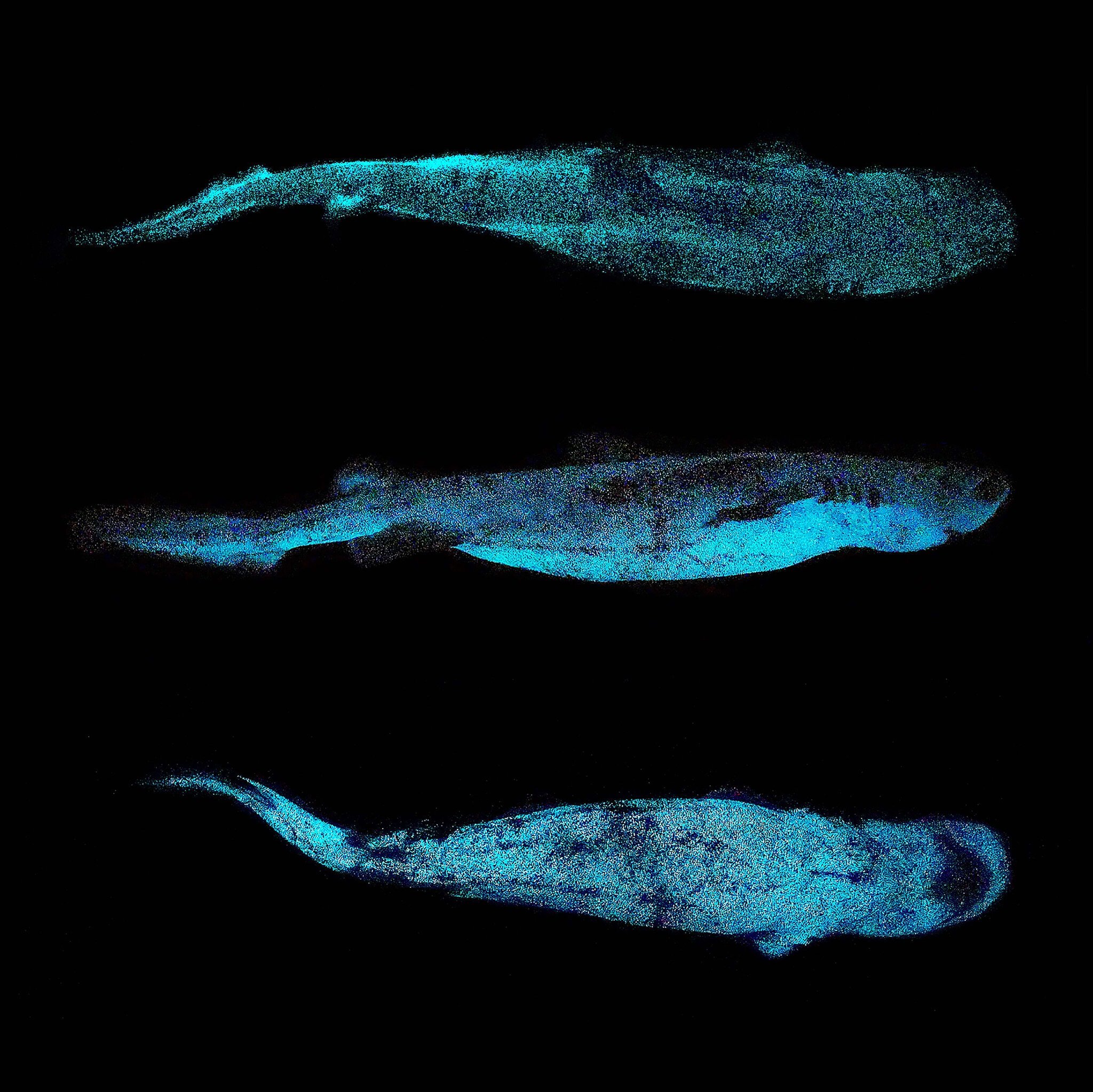

In addition to kitefin sharks, the scientists also examined blackbelly lanternsharks and southern lanternsharks - whose ability to light up has been previously documented. Once the shark's bioluminescence had been captured on camera, the scientists euthanized the fish and dissected skin samples to examine their illuminating organs.

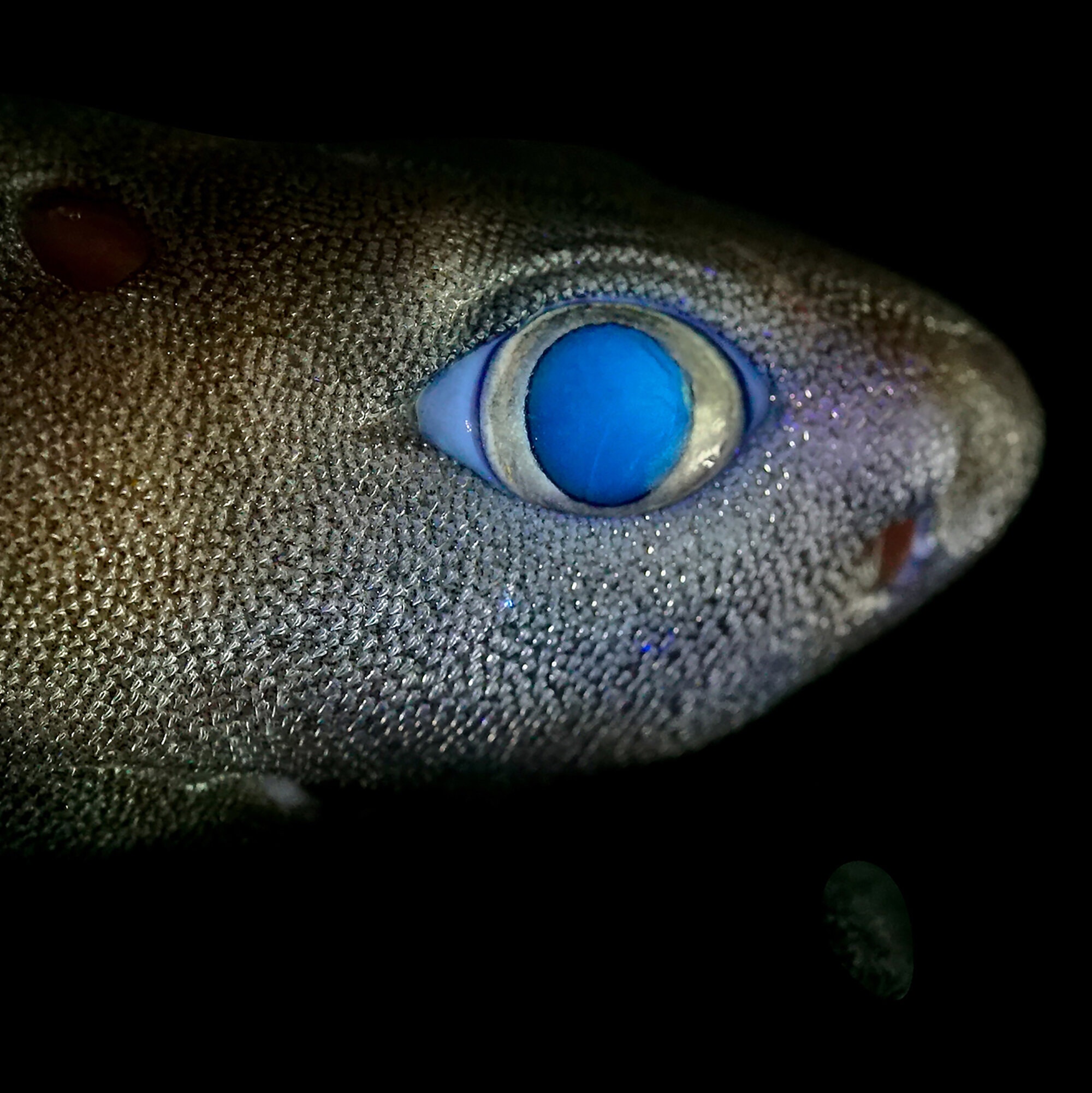

To their surprise, they discovered that unlike other glowing organisms — whose light-producing organs are controlled by their nervous systems — the luminescence in sharks is regulated by three hormones. Melatonin — a chemical that makes humans drowsy — triggers the glow, alpha-melanocyte stimulates it, and the adrenocorticotropic hormone shuts it down. The researchers still need to investigate what causes the release of the hormones.

The scientists think that the greenish-blue glow, which is concentrated around the bellies and undersides, helps the sharks blend in with the bluish light from above, providing the perfect camouflage. They speculate that it probably helps the tiny lantern sharks from being detected by predators. In the case of the kitefin shark, which has few predators, the natural glow may act as a flashlight to illuminate the ocean floor while searching for food. It could also help the massive, slow-moving species from being detected by potential prey. However, the reason for the light on the shark's fin is a mystery to scientists.

“The luminous pattern of the kitefin shark was unknown, and we are still very surprised by the glow on the dorsal fin," Dr. Mallefet says. "Why? For which purpose?”

The expert, who plans to return to the area to find other luminous creatures, hopes his research will inspire people to take measures to protect one of the least-studied ecosystems on the planet. "We hope by highlighting something new in the deep sea of New Zealand — glowing sharks — that maybe people will start thinking we should protect this environment before destroying it.”

Resources: Guardian.com, Sciencealert.com, NPR.com