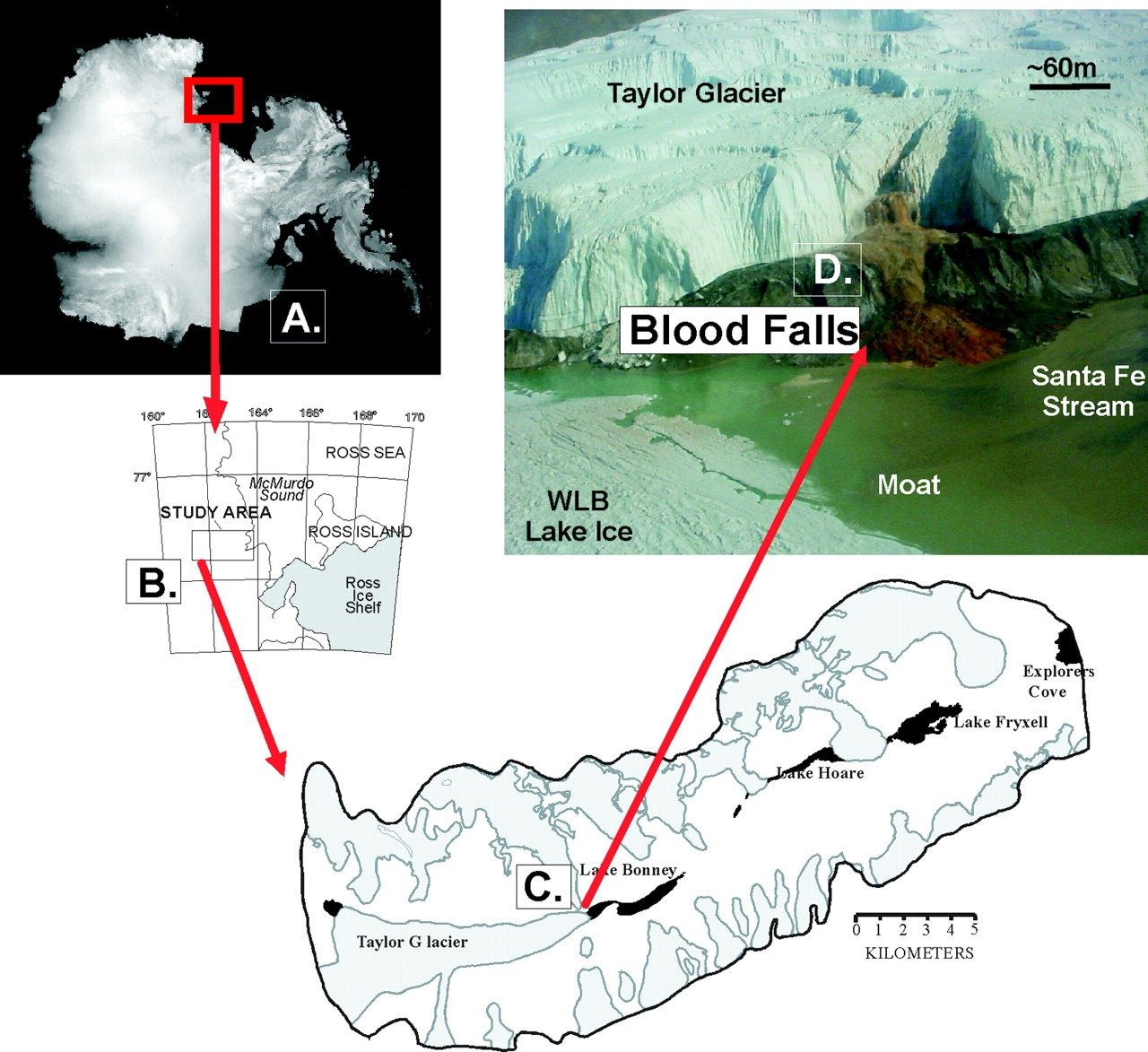

There are thousands of stunning waterfalls worldwide. However, none are as unique as Antarctica's Blood Falls. The aptly-named waterfall, which flows from the tip of the Taylor Glacier, spurts out bright red water. The existence of this five-story-tall waterfall has been known for over a century. But the reason behind its crimson waters has remained a mystery. Now, a team led by W. Berry Lyons of The Ohio State University may have finally found the answer.

Australian geologist Griffith Taylor discovered Blood Falls during an expedition in 1911. The explorer attributed its color to red algae. But further research invalidated this theory. Later studies asserted that the blood-red color was most likely from the iron in the subglacial lake that feeds the waterfall.

However, when Lyons and his team analyzed the water, they found only traces of iron. What they did find, though, were iron-rich nanospheres. The miniscule particles are 100 times smaller than human red blood cells. They are created by the micro bacteria that reside in subglacial lakes. The nanoparticles oxidize, giving the water flowing to the Blood Falls its distinctive red hue.

"As soon as I looked at the microscope images, I noticed that there were these little nanospheres and they were iron-rich, and they have lots of different elements in them besides iron – silicon, calcium, aluminum, sodium – and they all varied," said study co-author Ken Livi. "In order to be a mineral, atoms must be arranged in a very specific, crystalline structure. These nanospheres aren't crystalline. So the methods previously used to examine the solids did not detect them."

The researchers, who published their findings in the journal Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, believe their discovery may have implications beyond Earth. The subglacial lake that feeds Blood Falls is extremely salty, with no light or oxygen. This is similar to conditions on the Red Planet. Yet, it has managed to harbor an isolated microbial ecosystem for millions of years. This suggests there could also be life on Mars and other planets. However, we have yet to send the right equipment to detect it.

"Our work has revealed that the analysis conducted by rover vehicles is incomplete in determining the true nature of environmental materials on planet surfaces," said Livi. "This is especially true for colder planets like Mars, where the materials formed may be nanosized and non-crystalline. Consequently, our methods for identifying these materials are inadequate. To truly understand the nature of rocky planets' surfaces, a transmission electron microscope would be necessary. But it is currently not feasible to place one on Mars."

Resources: Livescience.com, Arstechnica.com, frontiers.org